What’s the difference between code switching and dog whistling? They are the same to me. Although each comes from opposite extremes, both are grossly involved in forms of naked self-denials. Each of us has a thing, a trademark that we carry in high esteem. Self-signatures of this flavor are seen as authentic tells shaping and pervading how others see or describe us, especially those we live with and work around. So, I have a confession to make–it’s one that I’m proud of but it doesn’t come easy–I don’t code switch! To hear that from an ethnically underrepresented academic philosopher sounds strange, I know, especially given that performance is one of the dominant and influential practices of our times? How could it be a good thing or even possible for me to suggest that being-oneself is the righteous way to go, even if one’s career is threatened or on the line? Promoting “keepin’ it real” culture strives to breakdown the communication disconnects we see across disciplines and to steer initiatives that professionalism seeks to promote away from policing our personal styles. I have experienced this to not only be good for company and institutional morale but I believe it to be a healthier, open, and better cultural exchange than the alternative of mass conformity.

Code-switching is anxious and repressive. As a cultural tradition, its purpose was to ensure that certain norms, mores, and customs were followed so that one was not deemed to be getting in the way or out of line. To be “straight,” in this sense, meant conforming to a blanket status quo. For this reason, I find the shame and blame game of cancel culture to be toxic and destructive, so I refrain from calling practitioners of code-switching “sell-outs.” Whatever justification they deem fit to move themselves into compliance mode, it is my hope they will reconsider engaging in this kind of theater charade; a charade in which the truth of the matter always lurks and haunts the pseudo-mask we wear around. Not being true to oneself, or as Jean-Paul Sartre called it bad faith,is a prerequisite to morally harm others, since there is a willingness to harm ourselves for some cheap material gain or upscale in social status. There is no question that status anxiety plays a major role in why code-switching looks appealing, and that means our capitalist competitions can easily turn into ruthless rivalries of jealousy and envy. But what if there was no way for others to want what you have because it is uniquely and intimately yours? That they could not have it nor enjoy it even if they tried? That is what character and personal ensoulment is all about and that is what one relies upon when refusing to obey the inhospitable praxis of code-switching.

For centuries, philosophers such as Erasmus, Montaigne or Nietzsche have warned against the dangers of being too forthright. Being too honest is a vulnerability—an open wound, so to speak. Everyday experience demands what Hegel called the “cunningness of reason” leading humans to acquire weapons and guns beforehand or in abstraco. In a world in which everything is on the move, we are tasked with acting in the vein of what Cameroonian political philosopher Achille Mbembe calls the “ethics of the passerby.” With this ethics the emphasis is placed, once again, on the importance of entertainment, hospitality, and manners as an essential means of cultural exchanges and rituals. Mbembe draws a crucial distinction between motivations and practices of social control compared with social grace. The latter has strong roots in several African traditions, like the South African Ubuntu practiced by the Bantu who hold as sacral the dignity (i.e., individuation) of every person as fundamental to justifying the legitimacy of human rights and equality within the community. Caring, sharing, generosity, and hospitality are the primary virtues of this moral philosophy that deems the worth of all human persons to be of the highest value. Is there any person you can say is ordinary and not extraordinary, even if they are the greatest villain or nemesis? Let everyone take off his or her mask—you are welcome here!

How are we oriented and situated to confront otherness–the strange and unfamiliar? Are we justified in being focused on “trust” or “control” in these unsettling encounters? The problem with social control is that it not only goes too far, but it doesn’t allow others the right or ability to build up social capital for themselves which is equivalent to a denial of self-determination. Code-switching or any system of imposing rigid standards of social conduct forcing us to act in Sartre’s bad faith is not only repressive on the person, but its debilitating affects extend to society as a whole. Oppressive subcultures do more damage than good when they do not allow for a wide form of tolerance and independence among its members. Microsoft recently learned this lesson when they opted out of a five-day work week for a four-day one in their Japanese locations and headquarters. It seems counterintuitive, but giving the workers an extra day off led to a surprisingly forty-percent increase in production. Now, I’m not saying this is a one-size-fits-all recipe that all companies, institutions, and nation-states should implement. Instead, I would like to stress how looseness rather than strictness is preferable to our professional lifestyles when it comes to the ethics of the passerby. Speaking in slang or jive, for example, is a disarming tactic. It makes the atmosphere and climate of the environment become warmer and illuminated. This also moves us in the direction of de-escalation rather than escalation and incitement, which potentially brings calmness and peace of mind. Readers will have to decide for themselves whether or not broadcasting confrontations and other acts of violence and dehumanization on social media will escalate or de-escalate the ethical dilemmas, or turn out to be more than spectacles of self-promotion. Putting on a facade of political correctness and code-switching leads to a boiling point, in which the tension becomes too great and parties are bound to snap. Ironically, code-switching is a vulgar form of escalation in the guise of de-escalation. Code-switching leads to eventual escalation and confrontational exchanges, especially when one can no longer live as a mannequin version of oneself. We improve our moral fitness once we aim to be flexible and lax rather than unyielding and uptight. This is the principle of mercy at the heart of social grace praxis that cultivates hospitality and patience.

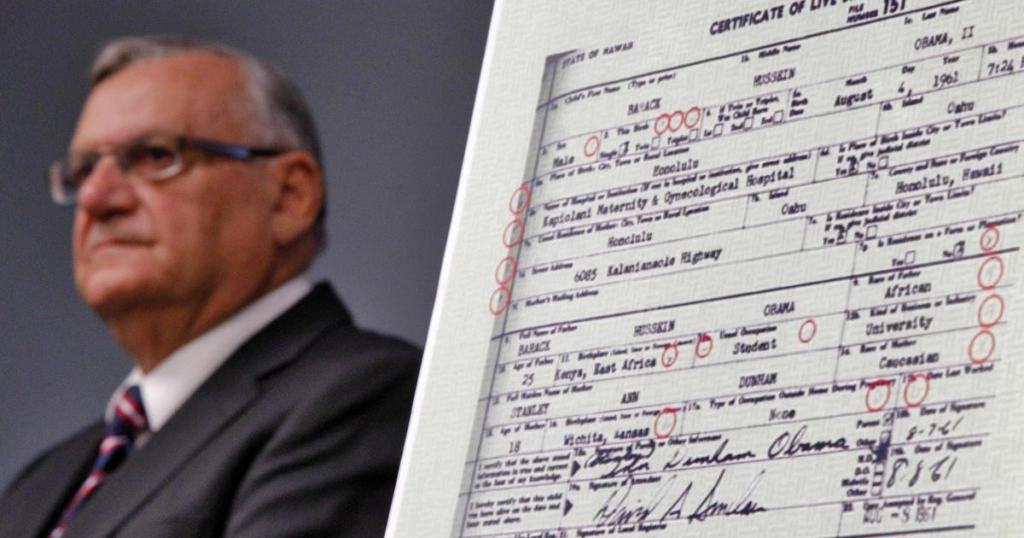

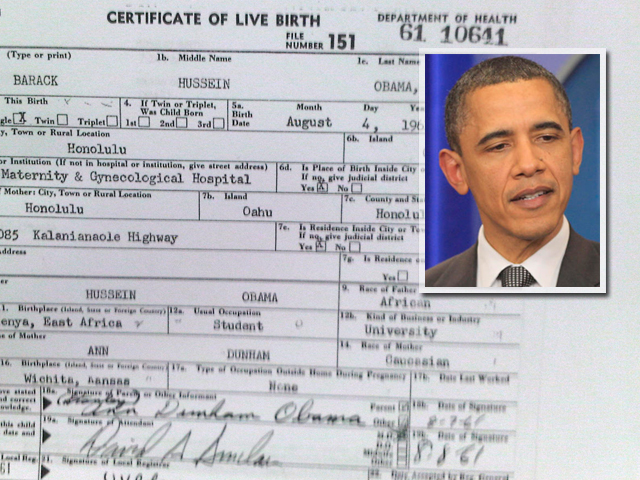

For all of his accomplishments and superior talents compared with the President who succeeded him, Obama is able to perform a smoothness that is parallel with an ethics of the passerby but he is a master code-switcher, as Ta-Nehisi Coates well pointed out: Perhaps no one has historically been a better negotiator of the “color line” than Obama. Although there may be an intention on behalf of Obama to practice social grace (“when they go low, we go high”), why does there appear to be a disconnect between the phrases and tones Obama uses in front of white and black audiences? The kind of two-facedness we associate with infotainment and theater democracy compels us to ask: who is the real Obama? The one singing Amazing Grace in front of African American churches in South Carolina or another who chooses to lay low and talk only in cryptic speeches while Trumpism (and Birtherism) runs amok?

Is there such a thing as virtuous code-switching? I have my doubts given how code-switching works to keep an unequal and repressed relationship intact. As is common from the standpoint of moral defeatism, a resolution of complacency becomes the catalyst for the code-switcher’s actions under the outmatched power structure. If we consider code-switching from the top-down rather than bottom-up, could this strategy of behavior ever be morally justifiable? Despite being a provocative thesis, I would contend that transparency is the key to breaking through the coldness that pervades the inability to be oneself. Being open and unguarded is a virtue I think leaders and management should pursue more. It humanizes the relationship beyond the anxieties over power and vulnerability. Without this compassionate appeal, work environments often become overwhelming and, in some cases, downright hostile. If a boss or manager were to “break the ice” by speaking in slang or showing a loose tone or unbuttoned side that could be a way to build positive meaningful relations, but I would call it code-switching in a positive sense. Get personal with someone! Be more open and looser, not closed and tight. That is the healthy form of code-switching that undercuts those socially constructed boundaries placed upon us by the professional world and expectation structures of success. I hold this view on two grounds. First, code-switching in the normal sense escalates tensions among “peers” and co-workers. Code-switching has the ironic consequence of escalating tensions while wearing the mask of de-escalation. Below the surface there is a rage of animosity and resentment building up, but how can we find alternatives that work to deescalate such counterproductive frictions? Second, the actor in acting out of character would be engaging in equalizing measures rather than unequal ones. Unlike code-switchers who accept things as they are, the boss or manager should be trying to minimize the rigidness of the power structure. One can claim that such efforts are merely performative since they do not ultimately remove the formal structures, but such an interpretation is overly cynical and works from a tragic, hopeless social ontology necessitating one’s motives and actions in a kind of misery and defeatism. Is your political philosophy and ethical principles enacted through a “front porch” or “backyard” social ontology of convergent/divergent interactions? For me, the front porch mentality represents a non-elitist mode of engagement and communal immersion without the pretense of something that acts as a replacement for one’s sincerity. There is a unique value of style and grace in just being oneself, beyond what one assumes or anticipates. It feels good to be oneself! Such intimate and non-imposing connectivity (the antithesis of “stand your ground” mentality) cuts across the need to dog whistle or code switch, which are ultimately cheap defense mechanisms in environments in which one does not feel welcome.