American Beauty

by Randall Auxier

Crispin Sartwell‘s book Six Names of Beauty is probably the broadest study of the idea of “beauty” ever written. It covers six different languages and their cultures (English, Hebrew, Sanskrit, Ancient Greek, Japanese, and Navajo), but also ranges across dozens of fields of meaning departing from each. Each chapter includes a dozen or more “mini-essays” of various length. They cover some application, implication, situation, or other “ation” of the name. I will offer an entry on each in this series, before moving on to the relation of art and life.

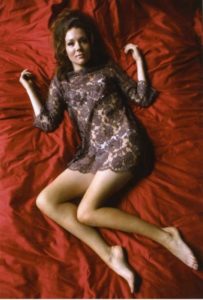

The (British) beauty on your left is Diana Rigg, who was the target of Sartwell’s youthful longing, and many other youthful longers, I would bet. But not me. Sartwell and I are about the same age, but he grew up in cosmopolitan DC, where they had British shows like The Avengers. I grew up in Memphis and we didn’t have cool TV shows, on account of all the Baptists. So I settled for Barbara Feldon, Agent 99. The Baptists couldn’t quite follow the innuendo and let that one through. But I didn’t tell anyone about my crush until now. I pretended it was Raquel Welch because my friends quietly pressured me to conform. Anyone can see Raquel was and still is stunningly beautiful, but she never “did it” for me, and here is the nub of the matter. It’s not just proportions or classical lines, or what everyone else finds attractive. There is an “it” that belongs to us alone. And there is something about longing for an impossible object (and let’s just admit we objectify these people) that does “it,” and can be wholly private and still satisfying. That longing has a power over us, a sway. Barbara Feldon was funny, in addition to looking like a cat. Yes, she was, uncomfortably, exactly the same age as my mother, Dr. Freud. Sue me. I moved on to the age-appropriate Valerie Bertinelli soon enough. She was funny too. It makes me think. (Everything does, but indulge me, will you?)

I first encountered the name “American Beauty” as a teenager. It was the name of an album by The Grateful Dead, displaying a rose on the cover. I bought it (for the song “Truckin'” not for the cover). I found out later that the name was from a kind of rose, a deep red, expensive, variety that is grown commercially in California, and is wildly popular in the US, but not much admired or grown anywhere else. I guess Jerry and the boys may have known that. They knew lots of things. The cover of the album is an ambigram, by design. It can be read as “American Reality” (as every fan of the Grateful Dead knows). The rose is open, inviting, and you could smell it if it weren’t made of cardboard. Some reality, huh? That rose is out of reach, but just barely.

Sartwell starts with these impossible objects of erotic longing and plows the whole field of connotations of the English word beauty, including discussions of death, make-up, saints, friends, and food. He explores whether beauty is subjective, discusses tools and the effort we expend in making beautiful things, notes how we respond to anything that is well-made. He pauses especially over Vermeer‘s painting Girl with a Red Hat, which lifted him above the mere eros toward Diana Rigg and into a more than objectifying consciousness. Something about that color red . . . But the mini-essay that caught my attention is a point about how we respond to intensity and power, even approaching the sublime, with a feeling we can call “beauty.” Seeing this iconic image of Diana Rigg made me aware that this image was repeated for the film American Beauty. That is the most screwed-up, twisted movie I can remember, even more so than Eraserhead, Requiem for a Dream, and Apocalypse Now. This is also the list of the most intense movies I’ve ever seen. It isn’t about pleasure or entertainment when you “like” these movies. I guess I liked them. It wasn’t similar to longing for Barbara Feldon. But the word “beauty” applies to all of them, frighteningly.

American Beauty attacked middle class ideas of beauty in America from every imaginable direction. We see one pathetic person after another, longing for what isn’t worth having. They are unable to stop themselves from acting on whatever the eye sees that the heart can’t live without. And that is the power of beauty: its power over us. The film places almost within reach whatever we fantasize about, and sometimes it is unsatisfyingly had. Chris Cooper’s character is the scariest –a retired Marine Corps officer who has concealed his homosexuality for a lifetime and evolved into the worst domestic tyrant in history. When push came to shove, all of the characters were tortured by the way beauty mixed with desire and held sway over them. But in the end, the central character (Kevin Spacey’s character) overcomes his sexual desire for a young girl and is freed from his fantasies and longing. He professes himself happy, even though he has been murdered, because “there is so much beauty in the world.” The exaggerations of these characters are only slight. There is an American Reality here. The movie won every award the world could give it.

One poster for the film was adapted from that image of Diana Rigg, it seems to me. There is just something about the color red that captures the intensity, the saturation, the power, the pain (and that is what passion means, suffering) and the longing that is “beauty” in English. We cannot help finding our way to the rose, the American Beauty rose, in deep, blood, red. Blood is actually blue in our veins and becomes red on contact with the air. I read that somewhere, but I think these associations with danger, death, bleeding from the thorn that guards the rose, this touches the essence of the matter for us, in this time, this place, this language.