Urd, or The Enigma Project

by Randall Auxier

You might not think you know this sentence, but you do: “Oy esd yjr nrdy pg yo,rd. oy esd yjr eptdy pg yo,rd/” I spent a couple of weeks in Poland this past summer, and for all the world, the language, lovely as it is, sounded very much like this reads. But in fact this is not Polish. Not even close. This is the result of my own Enigma Project.

If that name rings a bell, well, it should. Enigma was the name of a machine that created the top secret Nazi communication code before and during the Second World War. Having the machine that creates the codes was not, by itself, enough to break the codes. One needed to decipher protocols for setting the machine and many other things to break the code. The Nazis believed it couldn’t be done. But the Poles and then British were able to break the code. Seeing the war coming, the Poles shared their work with the Allies, and later the British were able to use this work and some of their own to decipher almost all German communications. So the Allies knew, in advance, some of the most sensitive and important information about German plans, strategies, troop movement, and spies. Obviously, if the Nazis suspected the code had been broken, they would have taken further steps to protect their communications, but the Allies were judicious in the use of the code. It affected the outcome of the war.

As I write this, I am currently sitting on a gigantic ferry that is crossing the Baltic Sea, surrounded by people who are speaking German (some are speaking Danish, but I can’t understand a word they say). Our ferry is leaving Denmark and will arrive on the German shore in about 45 minutes. I’m also actually in the middle of a train ride from Copenhagen to Berlin. They drive the whole damn train onto the ferry, empty it out. We all get a boat ride, and then pile back on when we get to Deutschland, to continue on our merry way. It occurs to me that if we stayed on the train while crossing, and something went drastically wrong, we’d be joining some U-boat crews on the bottom, sunk with the help of the cryptanalysts at Bletchley Park. And I suppose we would look very much as they must have, shortly after their demise, trapped in their long tubes in the cold water. Perish the thought.

The prospect of sharing Davy Jones’ Locker with some German sailors is not the reason I am thinking of the Enigma Project, or, as I now rename it: Yjr Rmoh,s {tpkrvy. It’s about re-entering Germany after what I saw in Poland. My project depends upon my own machine, in much the way that the Nazis depended on theirs. Their mistake was the sin of pride, or perhaps just arrogance. We all know German engineering prowess is second to none, so, you see, when Germans were Nazis, they made a machine. The code was kept inside a mechanism, and a set of protocols (books kept by all Enigma users), and all of it resided outside the brains and hearts of those who communicated with it. The communications were accordingly also mechanized. It was arrogant to believe that it would be impossible for an enemy to break the code. The Poles had effectively broken the code well before the war. The Germans had never quite grasped how good at math the Poles were, but they were better at it than the Germans, by a fair stretch.

The breaking of Enigma (and the Naizs’ failure to discover it had been broken) alone didn’t lose the war for the Germans, but perhaps arrogance of this sort was behind their ultimate military failure. Or maybe it was just something deep within the structure of perfect wickedness that undid them. In any case, information gleaned from the Enigma Project, along with other intelligence operations, probably added a significant advantage to the D-Day Invasion. Its success was far from assured, but I think its failure could have been guaranteed if the various misinformation and misdirection efforts hadn’t worked. The Allies knew where the Germans were (and weren’t) and the Germans did not know where the Allies would invade. It mattered greatly.

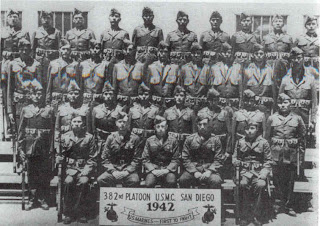

I attended a meeting in Poland where one of the featured speakers was Professor Joseph Margolis of Temple University. He was among the young allied troops who invaded France on that day, and he mentioned to me once that after the liberation of Dachau and Buchenwald, he found a good deal of personal purpose in the continued fight, since he is Jewish. For all I know, the Enigma Project saved his life –he was a paratrooper in the 82nd Airborne, I think. A lot of them didn’t come back. Joe Margolis’s twin brother didn’t.

I also visited Auschwitz on this trip. Afterwards I mentioned to a Polish friend that I felt all Germans should be required by law to go there and to see. You don’t really “get it” until you see, I said. And when you “get it,” you wish you hadn’t. One is face to face with the unimaginable. But my gentle Polish friend, although much younger, was wiser than I am. He said, “no, Randy, not just the Germans, everyone.” After all, I then thought to myself, as a citizen of the United States, it is not as if my own government is innocent of the crime of systematic, protracted genocide. At the time Frederick Douglass gave his famous speech (1852) about what the 4th of July means to a slave, he was, I believe, entirely justified to lay at the feet of the US government the charge of being the most evil power on the face of the earth, in its bestial, hypocritical murderous inhumanity. Every citizen of the US should be required by law to read it, I now realize. Or you can listen to someone read it, a survivor.

I also visited Auschwitz on this trip. Afterwards I mentioned to a Polish friend that I felt all Germans should be required by law to go there and to see. You don’t really “get it” until you see, I said. And when you “get it,” you wish you hadn’t. One is face to face with the unimaginable. But my gentle Polish friend, although much younger, was wiser than I am. He said, “no, Randy, not just the Germans, everyone.” After all, I then thought to myself, as a citizen of the United States, it is not as if my own government is innocent of the crime of systematic, protracted genocide. At the time Frederick Douglass gave his famous speech (1852) about what the 4th of July means to a slave, he was, I believe, entirely justified to lay at the feet of the US government the charge of being the most evil power on the face of the earth, in its bestial, hypocritical murderous inhumanity. Every citizen of the US should be required by law to read it, I now realize. Or you can listen to someone read it, a survivor.

I have been to Sand Creek too. It isn’t easy to think about. The strategy of concentration and removal, developed by the US government, was studied by the Nazis and praised by Hitler, according to John Toland‘s biography of Hitler (p. 202). It was deemed a suitable method for rendering a civilian population helpless. There was, after all, an American “final solution,” too, and the numbers involved were not so different, even if the period of implementation required many decades. Apparently Henry Ford also served as an inspiration, ally and friend to the Nazi cause. I don’t think it’s an aberration among Americans, I think we have selective memory regarding this period. Hitler had plenty of American supporters. And he still does.

Yes, my wise Polish friend, everyone should be required to go, and perhaps me most of all. And this indictment fails even to mention the co-operative European and Euro-American slaughter and enslavement of hundreds of thousands of the people of West Africa, and their subsequent history of rape, murder with impunity, and torture that followed upon it for hundreds of years. What began as the fruit of greed and an absence of legal control in North America came, over time, to be first carefully ignored, then legally allowed, then legally required, then a matter of centralized, bureaucratic planning, and then defended at the cost of hundreds of thousands of young lives. I speak not of Nazi policies but of American history, in terms general enough to accommodate both the institution of slavery and the genocidal policies toward Native peoples.

I most of all, and maybe you as well. Perhaps not all of us are “Nazis,” in the relevant sense. But there is no corner of the world untouched by this extended holocaust called colonialism and modernization. It continues today, in fits and starts, in small and large increments. Am I less arrogant than those who perpetrated the Nazi crimes with their hands and heads? I don’t know. It’s an enigma.

And there you have it. In this moment, riding across the Baltic Sea on a deck above a German train, I remembered that the US (which has never been especially adept at the spy game) managed to develop a code no one could break during the Second World War. Perhaps you know the story of the code talkers. I won’t retell it, apart from saying that the Navajo language is, evidently, pretty subtle and unrelated to other languages that would be known by the Axis Powers. To create a code in a little known language embeds the key in the living knowledge –in the minds and culture– of living human beings, not machines.

The indigenous code talkers wouldn’t be tortured for the code, if captured, because it would never occur to the (arrogant) captors to demand the code from them, specifically. They would assume we were as arrogant as every other “master race,” and I don’t know how wrong they would be, but we avoided one mistake: we didn’t mechanize our code. I don’t think that makes us better. Keep reading. Our code wasn’t failsafe. Nothing is. One code-talker could give away the secret and that would destroy the code as well as the idea for the code. But it didn’t happen. If you think through it, you may see why, but I will give you a hint: once the Japanese (for example) discovered that Native peoples were the source of the codes, what do you suppose would happen to Native peoples who were subsequently captured (whether they were really code talkers or not)? A still more uncomfortable thought: how different would that be from what was done to them by the US government, and every other government in the Americas? No, they didn’t give away the code. Would you, if you were in their place?

And this brings me back to the Enigma Project. There were plenty of ways the Nazis and the Russians and the Japanese and the Chinese, and even the French and British, could have created unbreakable codes using the languages of indigenous peoples within their own borders. It didn’t occur to them. In a way, the principle behind it did occur to the Nazis, but they made a machine instead of recognizing (diabolically?) that the human version, using, for example, the Sorbs, would be more secure. And that is why everyone should be required to visit Auschwitz. It is a giant machine, an Enigma Project covering many square miles. This picture is the concentration and work camp called Auschwitz I, where prisoners were tortured, twins and those with defects were experimented on, and Nazi doctors tried to figure out how to sterilize women belonging to undesirable races –this undesirability did not prevent rape (a point that may be made for the treatment of slaves in the Americas over a span of 400 years). Here they also determined by experimentation how much Zyklon-B was needed to kill an entire room full of people. The first test subjects were Russian prisoners of war and Polish dissidents. One thing I hadn’t known was that in the project to de-populate southwestern Poland and make it “fit” for Germans, the Nazis wiped out the entire leadership class of those provinces, murdering every mayor, city council member, teacher, professor, and civic leader in the region. By the end of 1940, they were all pretty much dead. Auschwitz wasn’t just for Jews: it was for dissidents, resistance fighters, the Romani, homosexuals, the mentally ill, the developmentally disabled, and anyone who got in the way. Undoubtedly, if there had been people of sub-Saharan African descent or Native Americans, they would have been included.

This is Auschwitz II, called Birkenau, a couple of miles away. This was the “death camp.” Only the women’s quarters are clearly visible. The men’s quarters were three times as expansive and the foundations are on the right in the picture. There was more space for men because they were more useful for working to death. Most women, and all children and old people were gassed upon arrival. The train station is lower right, and the strip through the middle is a massive platform, almost a mile long, where prisoners who survived the trip in cattle cars were sorted. In the upper left is where the gas chambers and crematoria stood. The Nazis blew these up as the Red Army approached. The Polish survivors decided to leave the remains of the buildings in the condition the Nazis left them. It is a sign of guilt when one tries to destroy evidence.

At first the Nazis thought they wouldn’t need to conceal their machine, because they expected to win and to proceed with the further plan to sterilize the Slavic women, and then move on to the gradual elimination of every troublesome source of difference. This is Crematorium 3 at Birkenau. There were five altogether, all blown up when they ran. You can’t get a sense of the scale of it since most of it was underground. They planted flowers outside and manicured the exterior sharply, to ease the prisoners into a sense of security. As you know, they were told they were going to the showers. There were signs and arrows pointing them in the right direction, “To the Showers.” All of it was, well, quite efficient, like clockwork in fact, and just as mechanical. They would require other prisoners to do the worst work –shaving heads before-hand, extracting gold teeth afterwards, cleaning the gas chambers. They would gas the prisoners who did this work every couple of months. They were witnesses, after all. One wouldn’t want the information to fall into enemy hands. But it’s hard to kill everyone.

Meanwhile, the American version of the Enigma Project was slower, more organic, but every bit as monstrous. Revealing its secrets requires that one ask an indigenous speaker. Here is Anne Marie Sayers. Maybe if you are very, very lucky, she’ll tell you a story. But you should ask in humility and you should listen until the story is fully told, and you should not interrupt, and you definitely shouldn’t argue. Pretend you’re at Auschwitz. Well, don’t pretend. You’re there, but you are talking to a survivor. I think every American (and I mean Americans –North and South) should be required by law to ask and listen for the full answer, and go away chastened to at least the same degree as any German citizen would be upon visiting Auschwitz. No, as I think about it, everyone should.

My ferry is docking on the shores of Germany, within shouting distance of the cities and towns that were reduced to rubble by British and American bombs. I need to change trains. But you may wonder about my little code. I will help you with it. The solution is very near to you. Very near. So close you can’t see it. And that is the whole problem. But I will help you this much, if you really care to know: The word in the title of this piece is “Yes.” You’ll know you have it figured out when you can read the familiar sentence I typed in code, and you’ll also know what I think about all of this, for whatever it’s worth.