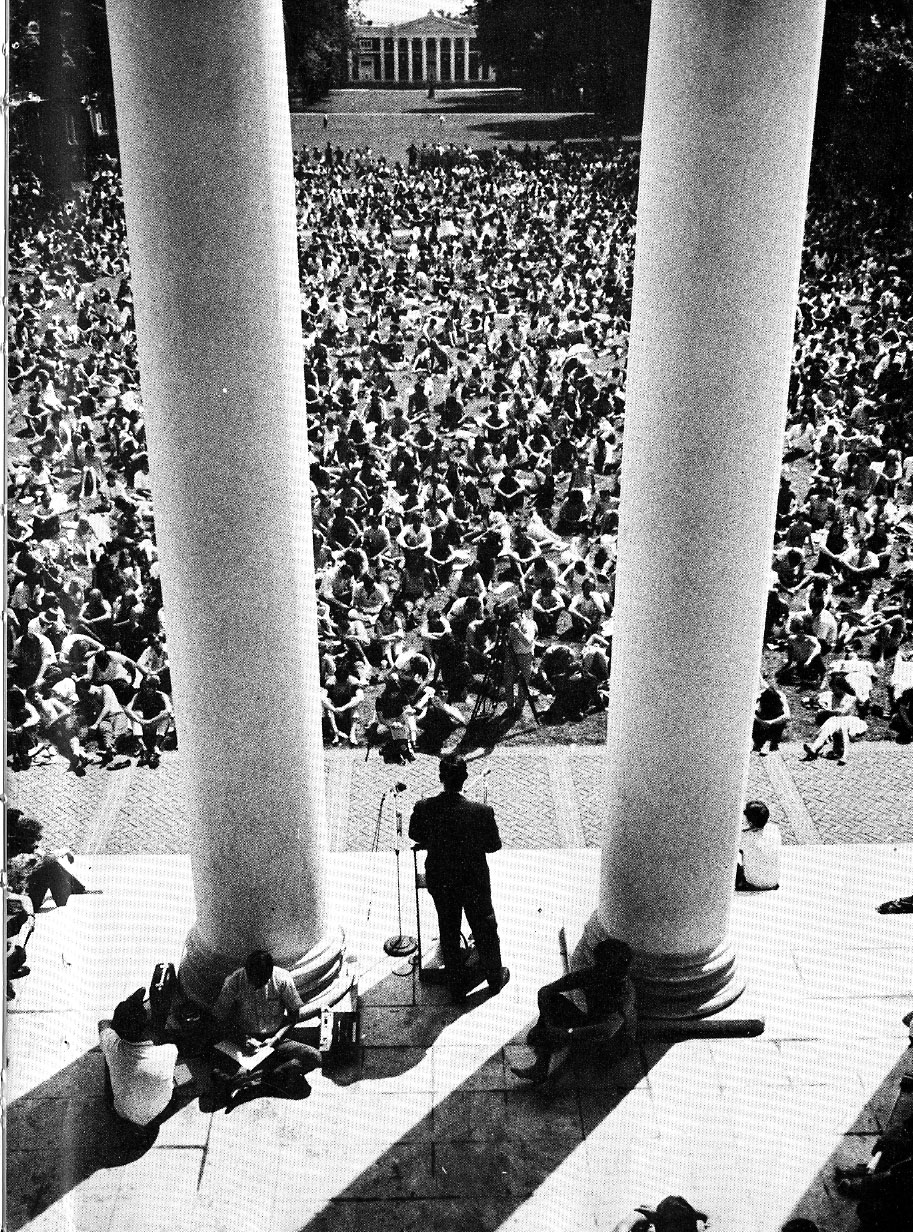

May Days 1970 at University of Virginia, photo by Andy Stickney, http://faculty.virginia.edu/villagespaces/essay/

The student protests in this country during the turbulent 1960s led by well-intentioned, idealistic young people, seem to have marked the death-throes of the American spirit. Directed as it was, unsuccessfully, against the “establishment” of materialistic, commercial and militaristic power that increasingly controlled this country, the effort sought in its blind way to breathe life into the spirit that had made this country remarkable. But blind it was, led by uneducated zealots who lacked a coherent plan of action, confused freedom with license, and targeted education which they barely understood and were convinced was turning into simply another face of the corporate corruption that was suffocating their country. In their reckless enthusiasm they decided that the core academic requirements at several of America’s leading universities were “irrelevant” and they bullied bewildered, frightened, and impotent professors and administrators into cutting and slashing those requirements. Other institutions were soon to follow. One of the first casualties was history, which was regarded by militant students as the least relevant of subjects for a new age they were convinced they could bring about by force of will and intimidation.

Had they been inclined to read at all, they might have done well to heed the words of Aldous Huxley when, in Brave New World, he pointed out that the way the Directors of that bizarre world controlled their minions was by erasing history. One of Huxley’s slogans, lifted from Henry Ford, was “history is bunk.” By erasing and re-writing history those in power could control the minds of the population and redirect the nation and determine its future. In the end, of course, the students who led the protests in this country and who thought history irrelevant were themselves (inevitably?) co-opted by the corporations and eventually became narrow, ignorant Yuppies, running up huge credit card debt and worried more about making the payments on their Volvos and their condos than about the expiring soul of a nation they once claimed to love. Or they became politicians tied to corporate apron-strings and thereby rendered incapable of compromise and wise leadership.

In 1979 Christopher Lasch wrote one of the most profound and informative analyses of the cultural malaise that resulted in large part from the failure of the protests in this country in the 1960s. In his remarkable book The Culture of Narcissism: American Life In An Age of Diminishing Expectations he warned us about this attempt to turn our backs on history:

“. . .the devaluation of the past has become one of the most important symptoms of the cultural crisis to which this book addresses itself, often drawing on historical experience to explain what is wrong with our present arrangements. A denial of the past, specifically progressive and optimistic, proves on closer analysis to embody the despair of a society that cannot face the future. . . . After the political turmoil of the sixties, Americans have retreated to purely personal preoccupations. Having no hope of improving their lives in any of the ways that matter, people have convinced themselves that what matters is psychic self-improvement: getting in touch with their feelings, eating health food, taking lessons in ballet or belly dancing, immersing themselves in the wisdom of the East, jogging, learning how to ‘relate,’ overcoming the ‘fear of pleasure.’ Harmless in themselves, these pursuits, elevated to a program and wrapped in the rhetoric of authenticity and awareness, signify a retreat from politics and a repudiation of the recent past. Indeed, Americans seem to wish to forget not only the sixties, the riots, the new left, the disruptions on college campuses, Vietnam, Watergate, and the Nixon presidency, but their entire collective past, even in the antiseptic form in which it was celebrated during the Bicentennial. Woody Allen’s movie Sleeper, issued in 1973, accurately caught the mood of the seventies. Appropriately cast in the form of a parody of futuristic science fiction, the film finds a great many ways to convey the message that ‘political solutions don’t work,’ as Allen flatly announces at one point. When asked what he believes in, Allen, having ruled out politics, religion, and science, declares: ‘I believe in sex and death — two experiences that come once in a lifetime.’ . . . To live for the moment is the prevailing passion — to live for yourself, not for your predecessors or posterity.”

If there were any questions about the spiritual health of this country, the loss of hope, the rejection of religion, history, and science, and the abandoned expectations of viable political solutions provide clear answers. We do seem to be a vapid people, collecting our toys and worrying about how to pay for them, wandering lost in a maze of our own making, ignoring the serious problems around us as we follow our own personal agendas — and remaining ignorant of the history lessons that might well show us the way to a more promising future.