“The Emancipation Blues”

by Randall Auxier

This kid is stealing licks. Or if not, there were a few hundred others just like him filching and pilfering until they could lay down a respectable imitation. Something just happened to the right of the camera, but this kid is ignoring it. He is studying those licks. We seem to be off in a rural place where livestock is sold (given the hay), and these well-dressed musicians would know how to choose a spot where coin is being exchanged. Note the top hat. That’s not for decoration. When on the move it sits on the bass player’s head –I’ll eat my hat if it ain’t so.

This kid is stealing licks. Or if not, there were a few hundred others just like him filching and pilfering until they could lay down a respectable imitation. Something just happened to the right of the camera, but this kid is ignoring it. He is studying those licks. We seem to be off in a rural place where livestock is sold (given the hay), and these well-dressed musicians would know how to choose a spot where coin is being exchanged. Note the top hat. That’s not for decoration. When on the move it sits on the bass player’s head –I’ll eat my hat if it ain’t so.

In this moment the crowd is thin and even the musicians are otherwise occupied, but this pair is doing a circa 1911 version of kicking out the jams. They’re good at the trade –past 30 years old and with clean white shirts and nickel cigars. They cut a figure. The kid thinks so. The bass may be homemade, but that guitar looks like a Martin 0-42. It was among the best back then. Very fancy. Still is. I wish I could hear what they’re playing, but I’d bet my bottom dollar it’s blues. No one is trying to save anyone’s soul here, but some folks are trying to keep soul and body together.

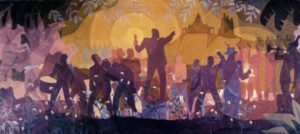

LeRoi Jones says that blues (strangely enough) came from emancipation. Prior to that, slaves were seldom alone, and even when they were, their music was censored by the masters and overseers. Nothing sad,or mournful, and of course, drums were strictly forbidden –they were effective for communication over great distances, after all. The last thing the slave economy wanted was rawhide texting. Rather, Jones says that only after emancipation did African Americans begin singing and playing as individuals. Only then could they travel, so that their experience ranged more widely than the immediate area of the plantation. Only then could they exchange and master their own vernacular and make their own troubles. Only then did they have access to high quality instruments, including drums. In short, the work song, the shout, the call and response, and the religious singing, especially, were the forms of music that could co-exist with slavery. And only after emancipation was African American music, which is to say the only original American music, freed from its (relatively recent) marriage to Christianity. The blues, ironically enough, is a genre of the free –both the “free to” and the “free from.” It’s the emancipation blues, and it’s sweet and soulful. Freedom’s just another word for . . . well, you know.

Jazz, on the other hand, is quite another story. Jones says that it is impossible to assign a birthplace to jazz, but then he spends most of a chapter discussing New Orleans. Ken Burns takes his cues from Jones and goes further, saying “Jazz grew up in a thousand places, but it was born in New Orleans.” He then spends the first episode showing us pictures and retelling Jones’s story, spliced with interviews of Wynton Marsalis and Herbie Hancock. I see Burns as being like that kid watching the guitar player above. It’s cool. He wants to do it too.

But jazz depended on freedom from the beginning. While it allowed slavery, the Crescent City was not part of the United States until 1803, and even then it took quite a while before it began to behave like a US city. In truth, it never really did. But due to its history of a couple hundred years as Spanish, then as French, and always as a port from which the whole world came and went, it was pretty difficult to identify racial separations. A large and economically successful French-speaking class of Creoles regarded themselves as (more or less) European. And of course they weren’t slaves. A large and economically depressed group of French-speaking sojourners ejected from Canada due to British war victories settled there and spoke a dialect that was shortened to the word “Cajun.” Escaped slaves, free blacks, white opportunists, mixes from the Caribbean, along with actual slaves and the usual mix of poor whites all converged.

The music they played stayed within their respective groups until Reconstruction ended. In the brutal restoration of local rule, Jim Crow was mandated, and New Orleans was a messy problem. The solution? Creoles, and anyone else with “one drop” of “impure” blood was effectively “black.” After all, the oppressors had to draw the line somewhere. They drew it at jazz. From that day forward, Jelly Roll Morton was an inevitable musician, the Creole jazzman who was “as good as black,” and who brought a musical education to a soulful sound he found at the docks. He also brought a deep sonic resistance to the dualization that was being imposed on his fair city –he and a hundred thousand jazzmen to come. Louis Armstrong perfected the mix, if Ken Burns is any authority.

The thrown-together mixture is what Wynton called “gumbo.” The music is different every night because every player who knows the basics can play it, but the musicians are different and the music itself is not repeatable. But it has a lattice, and a matrix, a dynamic form, that provides sonic space for improvisation. Individuals move forward in turn and work with the head, the theme, the changes. And as Wynton said, “everybody’s gonna eat some gumbo.” It isn’t black or white or creole, it’s delicious. If you think you wouldn’t eat the culinary products of a master chef who happened to be of a race apart from your own, Wynton and the jazzmen have news for you. You already ate it.

Stealing a lick isn’t so different from stealing a recipe, after all.