With Malice toward Some

Randall E. Auxier

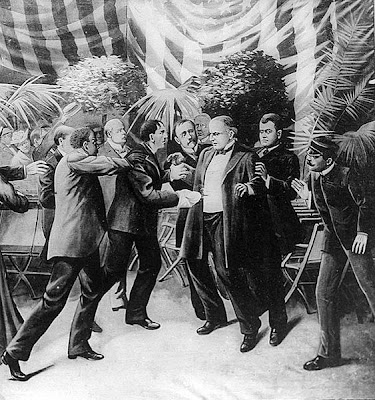

Leon Czolgosz is not a name people recognize. Yet, his act sketched above was a great turning point in American history (all of the Americas). The Republican Party had installed Theodore Roosevelt in the Vice-President’s office, an isolated deck of the ship of state, where a loose canon could do no harm, or so they thought. The McKinley administration continued suppressing unions and workers domestically, as Republicans are wont to do, and marauding among weaker peoples abroad, as was becoming the habit with both parties. Roosevelt would, if anything, intensify the marauding, but if there was one thing TR despised, it was the Captains of Industry. Two bullets from Czolgosz loosed Roosevelt upon the world, with three full years to effect a new order before having to stand for election. Could this change have been momentous even beyond the assassinations of Lincoln and Kennedy? We usually consider what we lost with those events, but do we dare think of what we gained from McKinley’s demise?

Could anyone have been elected US President expressing TR’s ideas about domestic reform? Would the rich and powerful allow it? Ponder the birth of the Progressive Era. It seems like a serendipitous victory for Czolgosz, since TR’s reforms favored people like Czolgosz, emigrants who were struggling in a brutal era of sweatshops and head-busting Pinkerton thugs. But I don’t know that Czolgosz would have welcomed the reforms. The press called Czolgosz an anarchist, and the scholars agree that he was reading a lot of radical literature, including the anarchist sort. People who called themselves anarchists, or were called that by various governments and the press, were taking a significant toll on the elite of the world, one bomb at a time. Assassination in that day was analogous to terrorist attacks today, great disruptors of the status quo, shocking the bourgeoisie, unimaginable deeds enacted in plain daylight. The fateful moment: Gavrilo Princip shot Franz Ferdinand, heir of the Austro-Hungarian throne, setting off the First World War. Princip was clearly a Serbian nationalist, but he was called an anarchist, which was the fashion by 1914, for anyone who went after the high value target at the expense of his own life.

The term “anarchy” was ever after doomed to association with reckless use of violence for unrealistic ends. That growing trend led Emma Goldman to explain, as well as she could, when and why people, including genuine anarchists, use violence to achieve political ends. Anarchism, as a political theory, does not cause political violence, she says. Bombing the unjust, as Ravachol and Vaillant did, or shooting a capitalist, as Alexander Berkman did, were akin to acts of nature, like the discharge of lightning to ground when too much of a charge has built up in the political atmosphere. But also, these men “paid the toll of our social crimes,” she says, and these heroes go to their executions as did the Christian martyrs among the lions of the coliseum. Goldman doesn’t mind singing the praises of such self-sacrificing people, but she wants to make it clear that it isn’t just anarchists who carry out such actions. Yes, some anarchists become violent and sacrifice themselves for the sake of the millions who suffer, but other sensitive souls, she says, do the same sorts of things.

The true anarchist is not hard to identify. Quoting from a notable psychologist of the day, Msr. Hamon, Goldman teaches: “The typical Anarchist, then, may be defined as follows: A man perceptible by the spirit of revolt under one or more of its forms–opposition, investigation, criticism, innovation–endowed with a strong love of liberty, egoistic or individualistic, and possessed of great curiosity, a keen desire to know. These traits are supplemented by an ardent love of others, a highly developed moral sensitiveness, a profound sentiment of justice, and imbued with missionary zeal.” She goes on, “To the above characteristics, says Alvin F. Sanborn, must be added these sterling qualities: a rare love of animals, surpassing sweetness in all the ordinary relations of life, exceptional sobriety of demeanor, frugality and regularity, austerity, even, of living, and courage beyond compare.” In short, these are the most admirable people any of us knows, not bloodthirsty killers.

The anarchist, then, is a lover, a sensitive soul, moved by profound sentiments. Goldman believed that Czsolgosz was surely such a sensitive sort, even if not a member of any anarchist group, as was the attempted assassin of the Chicago police chief, Lazarus Averbuch. But they, like so many others did not turn to violence because of any political theory; they acted as conduits of response to stop oppression. The entire argument leads me to wonder what Emma Goldman would say when the tide turned the other way, when right wing assassins joined the fracas, assassinating progressive leaders. Would she say that James Earl Ray or Sirhan Sirhan, or Nathuram Godse were also simply discharges of political lightning? Lightning occurs in nature when the positive and negative charges are separated, not when one charge is fed up with the other. And what about Von Stauffenberg’s effort to assassinate Hitler for the good of the Fatherland, as compared with Dietrich Bonhoeffer’s conspiracy to do the same thing for essentially non-nationalistic reasons.

Would Emma say, “well, there are different kinds of lightning?”

And would she say that the terrorist attacks of the last 20 years are somehow different from the bombings of the 1890s? I think she is right that theories don’t play as great a part in political violence as the media and the governments claim, and yet, I wonder whether she needed to look more deeply into her chosen metaphor. Do theories, such as anarchism, push people apart, ionizing the political and cultural air, or do such theories bring people together? I think such theories are divisive. Plenty of people who could live together quite well are driven into factions by misplaced abstractions. I don’t know whether the term “anarchism” can possibly be retrieved from the pigeonhole it now occupies, and why bother? The sorts of people described by Goldman’s psychologists haven’t disappeared, although they don’t generally call themselves anarchists. By the 1930s or so, persons who fit those descriptions were generally called “humanists,” such as Bertrand Russell, and, if they were especially self-sacrificing, the word was “humanitarians.” A great deal of unconventional behavior was tolerated from the likes of, for example, Albert Schweitzer.

On the other hand, Bertrand Russell and Albert Schweitzer were non-violent. The anarchists weren’t. Can an anarchist be a conventional person at all? What if that profound sensitivity to suffering and robust love of individuality happens to coincide with a preference for keeping a (conventional) bourgeois marriage? Could such a person still be an anarchist? Must all conventional people be neutrons in the political atmosphere, or might some be just the sorts of particles that prevent its ionizing, and coming to violence? Could Martin Luther King, Jr., (a very conventional person, in most respects) have been the effective leader he was if he were unconventional? Was his very conventional outlook on marriage, and the like, not the source of his support among so many?