Justice Clarence Thomas arguably shaped this court’s term more than any of his 30 years on the bench

After remaining silent during a decade of oral arguments, Supreme Court Justice Clarence Thomas drew gasps from the gallery as he started asking about constitutional provisions pertaining to the second amendment. Thomas rose back to life on Monday, February 29, 2016 and has been surprisingly talkative ever since. Upon completing his thirtieth term on the bench this past month it appeared that this once obscure jurist, notorious for subscribing to extremist views, rode off into the sunset. We can conclude that the highest court in the land is arguably no longer the “Roberts,” but the Thomas court. At least that was the impression of leading appellate litigator Paul Clement who recently remarked, “I don’t think Justice Thomas has ever had a better term.” Mr. Clement has argued more than 100 cases in front of the Supremes since 2000, more than any other advocate, including four this term with three being decided in his favor. He served as U.S. Solicitor General from 2005-2008. What were the big wins for the new Thomas court? Each had to do with deregulation or limiting the federal government’s authority over state sovereignty. In Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization (2022), the court upheld Mississippi’s law restricting abortion with only Chief Justice Roberts writing in his concurring opinion that he was not prepared to overturn Roe v. Wade (1973). Six conservative Justices struck down the Biden administration’s Clean Power Plan in West Virginia v. Environmental Protection Agency, ruling that the EPA exceeded its regulatory authority granted under the Clean Air Act (1970). And in a major victory for the gun lobby, (https://www.supremecourt.gov/opinions/21pdf/20-843_7j80.pdf) Justice Thomas penned the majority opinion in New York State Rifle & Pistol Assn., INC. v. Bruen, declaring New York’s concealed carry law unconstitutional. In a rare move, the court did rule 5-4 that it is legally permissible for the Biden administration to terminate the Trump policy of “Remain in Mexico.” How did America’s bête noire jurist become the judicial gold standard of our times? The answer has to do with the irony of judicial restraint and its philosophical adherence to originalism: judicial politics has been masked behind a relic of constitutional dupery. The politicization of constitutional rights has pervaded our social discourse, our private associations, and even our courts. Without any settled law, courts will continue to use adjudication as a vehicle to set the parameters for public policy while feigning to be apolitical. In sum, the Thomas court represents a new wave of American juristocracy.

Ran Hirschl’s Towards Juristocracy: The Origins and Consequences of the New Constitutionalism (2004) has been neglected and was well before its time. Hirschl tracks the growing trend of transferring unprecedented amounts of power from representative institutions to judiciaries. Through the case studies of Canada, New Zealand, Israel, and South Africa a new constitutionalism is seen to emerge. Juristocracy is the result of inept legislative and executive governance, which leads the judiciary to act as a default authority deciding what the constitution ultimately means. This predicament sounds eerily similar to the contemporary malaise political climate in the U.S. The imminent question becomes, as Bruce Gibney asks in his provocative book The Nonsense Factory: The Making and Breaking of the American Legal System (2019), “Judges: robots, umpires, or gods?” His book argues that Americans are victims of the arbitrary mood swings of judicial power. That our outrage toward police and legal abuses, such as police misconduct or state overreach is more a symptom of a legal system “gone wild.” Falling prey to money, corruption, and unjustified influences, Gibney attempts to argue that America’s legal system has descended into lawlessness, ironically. For far too long, jurists have been feigning to be apolitical, condemning the fray of ideologues and partisans in the realm of pure law. But this entire performance is guided by a perverse and shrewd pragmatism, rooted in an outdated doctrine of American civil theology. All of this despite the shady dealings which went on under the leadership of Kentucky senator Mitch McConnell’s leadership. The Republican-led senate thrusted itself into judicial politics once it chose the height of hypocrisy as the means by which to allow one nominee to get a hearing while another one didn’t. It was all politics. It is no mystery as to who will do the bidding of inept, crooked politicians—federally appointed judges. Beyond the cliché of getting “Borked” from the court, no one can deny that Bork was given a hearing and vote whereas Garland was not. Are we to conclude that this politics of the double-standard is an isolated incident? Hardly—that would be naïve. Increasing two-facedness pervades the jurisprudence of the right-leaning Supremes: beyond their well-rehearsed confirmation hearing claims that Roe is respected precedent or Alito’s leaked draft, there is a growing worry that the privacy rights most American’s take for granted will continue to be eroded. Justice Thomas said the quiet part out loud when he went out of his way in his Dobbs concurring opinion to warn that other civil liberties (e.g., gay marriage, contraception use) should not be considered as guaranteed protected rights by the federal government’s constitutional authority. States’ rights have become the cornerstone for an ultraconservative judicial philosophy guiding a majority of this court. What the constitution says and means is secondary to the more provincial ambitions stipulated through an unwavering commitment to state sovereignty and a performative originalist textualism. But fidelity to judicial restraint and a Scalia-like originalism may be more phantom and performance than a reality, especially given the glaring hypocrisies following several rulings this term. One in particular even startled Justice Keagan who remarked in her West Virginia v. EPA dissenting opinion: “Some years ago, I remarked that ‘[w]e’re all textualists now.’ [. . .] It seems I was wrong. The current court is textualist only when being so suits it. When that method would frustrate broader goals, special canons like the ‘major questions doctrine’ magically appear as get-out-of-text-free cards.”

Bruce Gibeny’s book The Nonsense Factory: The Making and Breaking of the American Legal System (2019)

We should not be surprised by such unchecked double-standards. Consider if someone came to you and said, “put me in the government so I can ensure that government remains limited and governed by the enforcement of deregulation,” would you believe them? In other words, would you be trusting enough to give those power who never detail or speak on how they will use it, other than preventing an overreach of governmental and legal authority? There was well-deserved pride recently as lawmakers from both sides of the aisle managed to pass gun reform legislation, a feat not seen in decades. Biden unflinchingly signed the bill. While the House overwhelmingly passed the measure, the Senate which has now become synonymous with the chamber where bills go to die, was able to muster a slim majority. Such legislative feats have become rare during America’s period of a do-nothing government—we have, sadly, grown accustomed to a listless leadership bent on doing nothing while emphasizing the things they cannot do nor support rather than telling us about the policies of which they approve. Floundering over the filibuster, for example, instead of addressing urgent problems has become the norm. Long gone are the days of “Yes we can.” It has become so pathetic that a normalized cycle of averting government shutdowns has taken over any semblance of business as usual. Each time the negotiations end in a budgetary quagmire and a temporary measure is passed until the next showdown to keep the lights on. The more we fall into the narrative of hyper-polarization the more our attitudes grow cynical and defeatist. Madisonian democracy is in perils once it becomes so inefficient that a detached efficiency is allowed to reign. Given our propensity for political gridlock, legislative victories are rare because compromise and bipartisanship are never easy. Since power was notoriously thought to corrupt those who possess it, Madisonian democracy was designed to promote the ironic virtues of inefficiency and open-ended, pragmatic government which does not desire any of the three branches to have the final word on what the constitution means. Compromises and other reasonable measures, in a pluralistic sense, must give way if anything “just” is going to be accomplished. But there is always the potential that we may regress and fall into disarray on all of our political fronts and be forced to turn to compulsory government, which operates mostly by non-democratic means. Which is to say, these procedures and practices are not opposed to democracy or should be outright deemed as anti-democratic but they do little if anything to work on behalf of democratic principles and values. In such leaderless, mediocre times it comes as no surprise to find the judiciary, the historically “independent and weakest” of America’s federal governmental branches (see Hamilton’s Federalist #78) to be leading the charge. In polarizing times, the most ideological and well-entrenched decide fait accompli.

Thomas’s shrewd opportunism reared its ugly face during those OJ Simpson trial-like confirmation proceedings over Anita Hill’s sexual harassment allegations. My mother, I recall, taped CSPAN’s exhaustive coverage of the hearings everyday as many families and friends got caught up in the high theater political drama. Here was the height of hypocrisy—a man dedicated in his black robe to being “colorblind” and racially neutral, which was largely deemed as accommodationist and working to solidify the status quo of white privilege, all the while using Ms. Hill’s allegations as a way to pull the “race card.” Thomas claimed to be the victim of a “high-tech lynching.” A claim which is hard to believe and fathom given that Thomas would be unlikely to give credence to such claims by any party bringing forth litigation before him. Thomas has consistently argued that racial preferences and considerations should not be applied in many important areas of constitutional law. Despite contributing to his own rise in the legal profession, Thomas is a stout opponent of affirmative action. Randall Kennedy, a frequent conservative critic of Thomas, complained about giving Thomas too many chances in his efforts to oppose anti-black racism:

Subsequently, I erred again. I argued that while Thomas is profoundly mistaken in racial policy, it is wrong to stigmatize him as a ‘sellout.’ But if Thomas is not a sellout, then the term has no utility. He is the paradigmatic figure whom many African Americans rightly despise—the black who, from a position of privilege attained by the sponsorship of powerful whites, consistently subverts struggles for African American collective elevation, all the while deploying his blackness as a shield against criticism (Say It Loud: On Race, Law, History, and Culture, 2021, 153).

Harvard Law School’s professor Randall Kennedy, often deemed a legal conservative by Black scholars, concludes after many years of wrestling with the issue, that Justice Thomas cannot be deemed as anything other than a racial “sellout.”

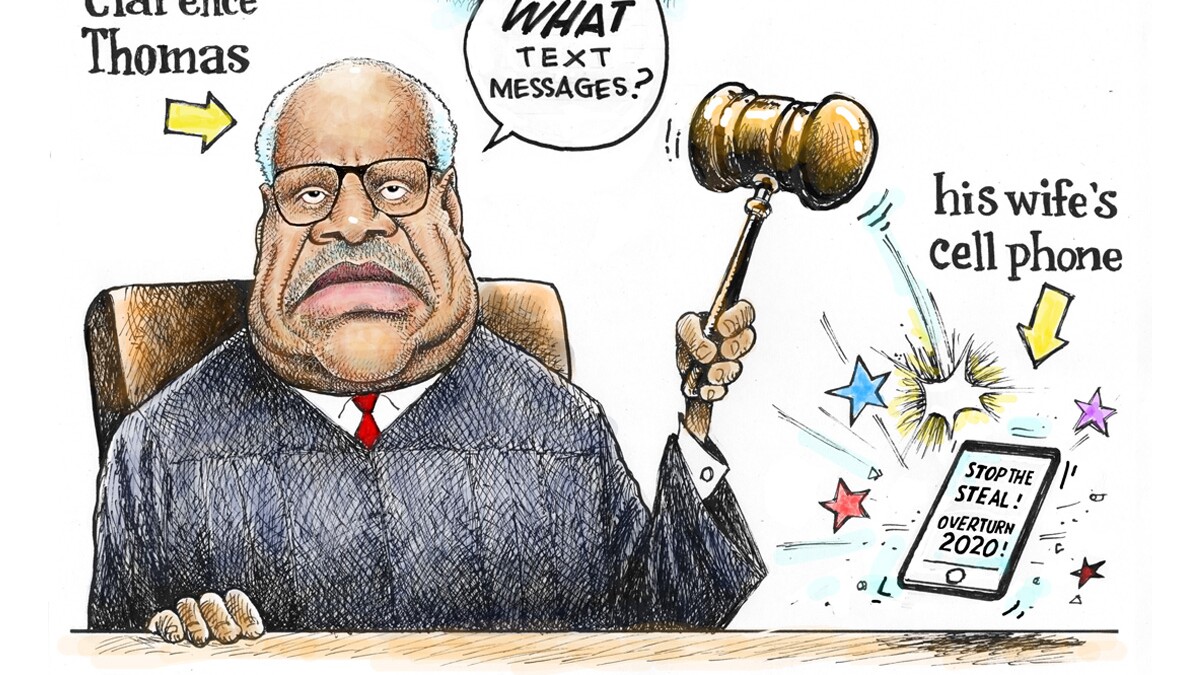

In January of 2021, the Supreme Court ruled against the Trump administration’s claims of executive privilege in efforts to ignore Congressional subpoenas requesting records and communications concerning events about the January 6th insurrection. While Chief Justice Roberts openly claimed that the courts were “jealously independent,” chiding Trump after his aggressive tweets about the American judiciary being “corrupt and rigged,” Thomas was the lone dissenter in these complaints. Did he have a dirty little secret and know that Ginny Thomas was sliding in so many DMs? This is a serious matter given the nature of the allegations. For example, I venture to argue that getting to the bottom of these communications is more urgent than discovering who leaked Alito’s Dobbs draft, which the court has still never discovered or released. Several lawmakers, including Illinois senator and judiciary committee chairman Dick Durbin have unrealistically called upon Justice Thomas to be impeached. Others have more modestly asked that Thomas recuse himself from any cases involving the Trump administration, given his compromised tangibility with those issues. Although it is expected that nothing will come of these mounting complaints, there is little question that Justice Thomas has sabotaged much of the court’s trust and legitimacy. Despite his wife’s claims about being eager to meet with the January 6th committee in an effort to “clear her name” from any wrong-doing, efforts have been made to shield her from answering any questions. To say this is a conflict of interest would be an understatement and the longer this issue goes unaddressed the more Justice Thomas should face inquires about his own dereliction of duty.

In a series of 8-1 rulings, Justice Thomas sided with the Trump administration’s efforts to challenge the 2020 presidential election results before the public discovered that his spouse, Ginny Thomas, was frantically contacting public officials in several states, including White House Chief of Staff Mark Meadows to “stop the steal.”

All of these difficulties have mounted into a whirlwind of constitutional uncertainty and troubling forms of what Zygmunt Bauman called retrotopic thinking or the naïve view that “wisdom and exemplary models of right conduct” can only be discovered and respected from the past, never in the present or the future! Americans increasingly face a juristocracy resembling a Janus Head suffering from Van Gough’s affect—instead of an ear, the forward-looking face is lopped off. A continued fallacy of the Republican movement is the commitment to believing that what was before is self-evidently superior. Why else mess with a 50-year-old legal precedent like the right to abortion, which justices were eager to claim as “settled law” during their senate confirmation hearings? One of the philosophical limitations of retrotopic juristocracy is its willingness to commit unforced error by stepping away from what has been experienced, achieved, and practiced into what merely feels comfortable, familiar, and acceptable. Such inconsistent loyalties are growing common and, as we confront an age more committed to disloyalty than loyalty, we must reject any “originalist” jurisprudence pretensions. Such performative and lifeless interpretations mask—call it, constitutional charades—the vulgar opportunism at work. Indeed, Justice Thomas stirred the pot as a lead instigator who encourages fellow justices to make an all-out assault on the penumbra of American privacy protections by claiming that the court should re-litigate (instead of re-legislate) the last century of settled law in this area. Justice Thomas took issue with three cases which he finds to grounded on similar flawed legal reasoning: Griswold v. Connecticut, a 1965 decision that declared married couples had a right to contraception; Lawrence v. Texas, a 2003 case invalidating sodomy laws and making same-sex sexual activity legal across the country; and Obergefell v. Hodges, the 2015 case establishing the right of gay couples to marry. His concurring opinion in Dobbs argued that “In future cases, we should reconsider all of this Court’s substantive due process precedents, including Griswold, Lawrence and Obergefell.” The Justice was silent on the issue of interracial marriage.

Given Thomas’s newfound pivotal influence, the most important cases on the court’s docket for next term involves affirmative action in higher education and the partisan gerrymandering case in North Carolina. Moore v. Harper will revisit the issue of inside politics behind gerrymandering, which jeopardizes any integrity and sincere efforts to respect proportional representational equality. Students for Fair Admissions v. Harvard will revisit the issues of racial preferences used in admissions practices upheld as constitutional in Grutter v. Bollinger (2003). It will come as little shock to discover that the court’s conservative majority has consistently opposed such preferences as discriminatory and legitimizing bias. The conservative bloc prefers to pretend we live in a post-racial society or to approach racial tensions with something akin to John Locke’s tabula rasa.

“There was no need for the court to take this case because there was no disagreement in the lower courts. So, this is not judicial restraint,” says Mary Ziegler speaking of the Dobbs ruling. “This is the court wanting to do this.”

Protected civil rights we have largely taken for granted are under threat as more justices work to approve Justice Thomas’s prerogative to turn back the national clock. To say that court commentators are dumbfounded would be an understatement as senior editor for Slate, lecturer at University of Virginia law school and “Amicus” podcast host Dahlia Lithwick was asked if she ever witnessed the court in its current state: “I have not. And I want to say that with the caveat that so much of what we think we know, we don’t know. In other words, none of us who are watching what’s happening are, in fact, the nine justices that we are describing. And so a lot of what I am reading is what you’re reading and what Amy’s reading, which is speeches such as Justice Thomas’s or, you know, the leak and the succession of leaks that came after. And the really good reporting that’s been done about what it feels like inside the court, how the clerks are feeling. And so, given all that, I’m confident in saying I’ve never seen anything like this, and I’m also confident in saying I don’t know what I don’t know. And it may be just peachy inside the conference room where the nine justices sit, and work together and maybe we are reading too much into it.” Legal historian Mary Ziegler was asked if she thought this was more of a cavalier court or one that truly abides by judicial restraint. She responded by admitting that “any reasonable person will think this is a partisan decision, in part because the court has done nothing to deter that. This is not something that the court took its time in doing. There’s no reason the court needed to take this case. The language of the opinion is unnecessarily divisive. We can’t know what was inside the justices’ minds, but we can know that the way they decided this will do nothing to dispel the idea that this is partisan. And that’s sad. It’s not good for the United States for people to be losing faith in all our democratic institutions, including the court.” Her analysis calls to mind a recent poll taken before the end of this court’s term reporting that public confidence in the Supreme Court has sunk to historic lows (https://news.gallup.com/poll/394103/confidence-supreme-court-sinks-historic-low.aspx). No one can be certain what Justice Thomas’s majority will scrap next or how it will play out, but we do know it’s been a long time coming. How many of us are eager to hear what they have to say or finding out which groups will have to pay?

When the Legislative and Executive powers fall into great paralysis, a semblance of democracy results known as Juristocracy