Maddening Masculine Mystery

by Randall E. Auxier

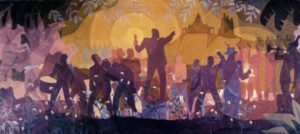

Here we have an image from the height of the Harlem Renaissance. The painter is one Aaron Douglas. His images are iconic, defining the era, the atmosphere, the edges and the center of black self-consciousness in the 1920’s and 1930’s. This is one of the most famous. It depicts the African American experience from the jungle to the State House. But, wondrous as the image is, look closely. There are no female figures. Apparently the African American experience is just the experience of the “men” of action. The clear message is activism, of every kind. No passivity.

Here we have an image from the height of the Harlem Renaissance. The painter is one Aaron Douglas. His images are iconic, defining the era, the atmosphere, the edges and the center of black self-consciousness in the 1920’s and 1930’s. This is one of the most famous. It depicts the African American experience from the jungle to the State House. But, wondrous as the image is, look closely. There are no female figures. Apparently the African American experience is just the experience of the “men” of action. The clear message is activism, of every kind. No passivity.

Douglas was a man of his age, and it carried a weird orthodoxy, quite beyond anything we now associate with race consciousness. In those days, whatever artistic productions were packaged so that both black and white audiences might pay to enjoy it was dubious, even “blackish,” although that terminology didn’t then exist. What did exist was a male-dominated purity cult and an ethnocentric demand that left the likes of Zora Neale Hurston on the margins. The artists were supposed to lead the race to a new day –musicians, painters, writers, poets, speakers, stars of the (then burgeoning) black theater, and even the nascent film companies.

Today, whenever anyone mentions Hurston’s name, many people genuflect. But it wasn’t always so. Richard Wright, who was generally seen as the literary center of the Renaissance, excoriated Hurston for being pandering to white readers and their harmful stereotypes. Listening to his diatribe, one would think she was the single-handed cause of whatever ailed the black race. But holding back a whole race turns out to be a complex undertaking. I wish I, for one, actually knew how to pander to whites. You know, affect their views about race for the better. I don’t see how anyone could make things worse, in 1937 or now. What if someone presents them with a black woman driver of one of those so-called “stock cars” and she drove it at 200 mph around a banked track, in some redneckish piece of rural real estate . . . well then, now, now one has approached the inner sanctum of the white-bread heart. Even Zora, with all her insight into human nature, couldn’t have seen NASCAR on the horizon, but if she were alive today, she might try it. She was bold. It got her in trouble. Repeatedly. She didn’t care.

But she also never cared one whit about race (or so she repeatedly said). Her obsession was the difference between the masculine and feminine, and in a only secondary, or tertiary way, some manifestation of that mystery in our time and place, some present permutation to mock us in our impotence to make the differences dissipate. Race is a current problem, chronic and difficult, but compared to the battle of the sexes, it’s a side show. I think I get that, in my masculine way. I certainly never saw a learning curve quite so steep as understanding the other gender. Compared to this monster on the mountain, race, by comparison, seems like more like a housecat of a problem (granting, it’s a mean cat). Let that problem wind around your legs, feed it, and hope it doesn’t eat you one day, where you dropped dead in the lonely apartment of being. Make peace with the mean cat, but stay away from that mountain. Don’t go up there.

We probably wouldn’t know anything about Zora if not for the efforts of Alice Walker and Oprah Winfrey. They resurrected Zora from just keeping company with Marie Laveau (and all her sisters, floating above their graves). Zora, they believed, was for the living. She was the anthropologist as well as the voodoo queen, the writer as well as the witch, and the blackish label pinned on her by Richard Wright wasn’t to be the last word conjured over her bones. So, in about 1984, Oprah and Alice held a seance of sorts (what is our mass culture, if not a huge seance?), and all of a sudden the (black) mystical, divine feminine was back. And it had a name: “Zora.” She became the darling of a whole generation of woman writers, even if not all had brown skin. And she was so much more –a singer, a dancer, a playwright/producer/director, acting in her own productions, an all-around artist. When she was ruined in Harlem, she made a living putting on shows she created in central Florida, including the first real all African American folk opera (Porgy and Bess came three years later, and might have been inspired by The Great Day). She was a pop culture factory, forty years too soon.

That might have been the end of the story, except that, well, the works were brilliant and beyond brilliant. Anyone who reads Moby-Dick today has difficulty believing that the critics and contemporaries of Melville panned the book –and that book simply disappeared from 1851 until 1920 or so. The assholes buried Melville. They buried him. They convinced him to quit writing novels. He lived miserably afterwards, knowing, inside himself, that he had produced one of the greatest novels in human history and enduring the scorn or worse, complete neglect of everyone who might have a shot at seeing what he had accomplished. Same with Zora. She wrote the truly great stuff, individual sentences Shakespeare would have envied. And there sat the assholes, asking whether she was pandering to white people. Richard Wright had the temerity to say she had no interest in serious fiction. Jesus. Truth is, she was a woman who did just as she pleased, smoking her cigar, to the consternation of every “godly” man who wanted to keep her down.

Beneath all this static, there is a seldom discussed problem. It appears in writers like Hurston and in Walker, and Toni Morrison, and Sue Monk Kidd, and Amy Tan, the list goes on. Tales of the Sisterhood, one might call them. There is a scary and deep-seated battle of male and female at the heart of African American culture, just as surely as within every culture (and subculture, and city and household). It was not an accident that Zora was a woman who refused to be tamed while Richard Wright was a man who attacked her for not getting “with the program.” I wish the results hadn’t been so dire for Zora, but she never pitied herself, no matter how bad things got –and things got bad. The men of the Harlem renaissance made it impossible for her to make a living, at least in their environs.

There was a violence between man and woman that defined the experience of emancipation to Great Migration, but the violence was only the outer appearance of the spiritual struggle. That deeper conflict can only be grasped as symbol. Janie Stark, the lead character in Hurston’s Their Eyes Were Watching God, shuffles through every male type, and upon finding her true love, goes to ruin. The perfect man is, in the end, rabid. He has always been on the edge of giving in to the white man’s depravities, but in the end it is the combination of nature and the insanity of the white man’s best friend, the mindless servants of the Way Things Are who infects the deepest part of the black masculine mind and soul. There is no helping him. He must be shot. And afterwards, what remains of black masculinity? Whatever the women can conjure.

No wonder the black men didn’t care for Zora’s depiction of their strengths and foibles. No one wants his own essence on display, even in the hands of the ungentle witch queen of New Orleans. She likes you or she doesn’t, and you don’t get to say which. And then she writes the story her way, with all your goods on display, a masculine mystery no more.