Liverpool Cool and the Ivi League

by Randall Auxier

Picking up from Troubadours 1, a great part of what makes a song communicate to one’s ass happens below the level of lyrics and melody. Sometimes a troubadour can sacrifice lyrics and/or melody to this sort of below-the-waist movement of musical truth. (Chords and melody are, at most, the top half of the deal.) Sure, powerful melody, interesting chords, and lyrics are a plus, but even then, an amazing bass line does more to affect your mood. I mentioned Jonathan Cain’s driving left hand in the Journey song “Don’t Stop Believin’” and how that freed bassist Ross Valory to ask “what can I do for the whole?” I traced a strategy I will now call “the Liverpool School” to Paul McCartney‘s innovations. Possibly his greatest disciple is Sting. They are Liverpool cool.

Picking up from Troubadours 1, a great part of what makes a song communicate to one’s ass happens below the level of lyrics and melody. Sometimes a troubadour can sacrifice lyrics and/or melody to this sort of below-the-waist movement of musical truth. (Chords and melody are, at most, the top half of the deal.) Sure, powerful melody, interesting chords, and lyrics are a plus, but even then, an amazing bass line does more to affect your mood. I mentioned Jonathan Cain’s driving left hand in the Journey song “Don’t Stop Believin’” and how that freed bassist Ross Valory to ask “what can I do for the whole?” I traced a strategy I will now call “the Liverpool School” to Paul McCartney‘s innovations. Possibly his greatest disciple is Sting. They are Liverpool cool.

That School is strong in England, but its origins are American and African and Caribbean, just like most rhythm-driven pop music. Followers of McCartney like thick sounds, lots of high and mid-neck descending scales, and saving the lowest notes for a moment of release. John McVie is English, of course, but so are others you’ve heard a million times but you may not know their names: Dee Murray (Spencer Davis Group, Elton John Band) and John Deacon (Queen). These two masters of the mid-neck had the advantage playing with amazing keyboard players (Steve Winwood, Elton John, Freddie Mercury).

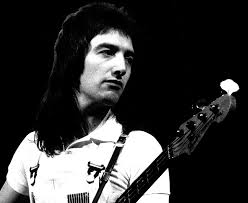

That School is strong in England, but its origins are American and African and Caribbean, just like most rhythm-driven pop music. Followers of McCartney like thick sounds, lots of high and mid-neck descending scales, and saving the lowest notes for a moment of release. John McVie is English, of course, but so are others you’ve heard a million times but you may not know their names: Dee Murray (Spencer Davis Group, Elton John Band) and John Deacon (Queen). These two masters of the mid-neck had the advantage playing with amazing keyboard players (Steve Winwood, Elton John, Freddie Mercury).  When a bassist is lucky enough to play alongside a keyboardist with a strong left hand, it frees the bass guitar to compose, to accent, to explore, basically to choose. Paul McCartney’s explorations on “Don’t Let Me Down” (mentioned last week) were aided by Billy Preston‘s left hand. The keyboard can carry the root of the chord like a guitar cannot. I won’t belabor the Liverpool School except to say you should give a listen to the bass lines on “Rocket Man” and, most impressively, on “You’re My Best Friend,” a song John Deacon composed (he also played the signature synth line on it). You may think it’s a simple pop song, but listen to the bass line. Now notice the musical layers. You may want to rethink that opinion. Musically it’s a symphony, as with so many other compositions by Queen.

When a bassist is lucky enough to play alongside a keyboardist with a strong left hand, it frees the bass guitar to compose, to accent, to explore, basically to choose. Paul McCartney’s explorations on “Don’t Let Me Down” (mentioned last week) were aided by Billy Preston‘s left hand. The keyboard can carry the root of the chord like a guitar cannot. I won’t belabor the Liverpool School except to say you should give a listen to the bass lines on “Rocket Man” and, most impressively, on “You’re My Best Friend,” a song John Deacon composed (he also played the signature synth line on it). You may think it’s a simple pop song, but listen to the bass line. Now notice the musical layers. You may want to rethink that opinion. Musically it’s a symphony, as with so many other compositions by Queen.

But another school is cooler (IMNSHO). I call it “Immigrants, Voluntary and Involuntary,” or for short, the Ivi League. This group of lefties (in every sense of that word) were mainly either African American or Jewish (although the latter often changed their names to seem less ethnic in a WASPy world). During the crucial days of the early 20th century, before the transition to electric music, and back when when the sound of American commercial music was really being formed, the key figures played piano. There was Scott Joplin and the left-hand striders like James Johnson. These guys are bass players, a generation before the electric bass was invented. I will take up their story in the next blog. But my Ivi League bassists went to school on those earlier legacies (who were also immigrants, both voluntary and involuntary).

But another school is cooler (IMNSHO). I call it “Immigrants, Voluntary and Involuntary,” or for short, the Ivi League. This group of lefties (in every sense of that word) were mainly either African American or Jewish (although the latter often changed their names to seem less ethnic in a WASPy world). During the crucial days of the early 20th century, before the transition to electric music, and back when when the sound of American commercial music was really being formed, the key figures played piano. There was Scott Joplin and the left-hand striders like James Johnson. These guys are bass players, a generation before the electric bass was invented. I will take up their story in the next blog. But my Ivi League bassists went to school on those earlier legacies (who were also immigrants, both voluntary and involuntary).

I promised last week to “make you love the rule,” by showing you the exceptions first. Here’s the rule: Normally the bass pounds on the root note of the chord and hits it precisely with the first and third beat of each measure, matching the kick-drum. The thud and the plunk reinforce each other and present a formidable frame and motive for moving your ass. The accent beats on two and four are owned by the snare drum and the rhythm guitar. They oppose the movement of the bass with a counterpoise, a chop, a halt between steps. The magic is in the variations that are built on this frame.

I promised last week to “make you love the rule,” by showing you the exceptions first. Here’s the rule: Normally the bass pounds on the root note of the chord and hits it precisely with the first and third beat of each measure, matching the kick-drum. The thud and the plunk reinforce each other and present a formidable frame and motive for moving your ass. The accent beats on two and four are owned by the snare drum and the rhythm guitar. They oppose the movement of the bass with a counterpoise, a chop, a halt between steps. The magic is in the variations that are built on this frame.  Heavy rhythm songs generally keep bass and kick exactly together. Listen to “Pump It Up” by Elvis Costello,” or, for a lighter version, “And She Was” by Talking Heads (where the bass lays out every other measure). You can really hear the rule’s effect here. Or try the Doobie Brothers‘ “Takin’ It to the Streets.” (All of those bands had truly great bassists.) Also worthy of a listen, for variations, is the bass line to Paul Simon‘s “Me and Julio” and all of the bass lines on his Graceland album (pointing back to the African origins of these rhythm combinations). For something a little more recent, try Rusted Root “Send Me on My Way.”

Heavy rhythm songs generally keep bass and kick exactly together. Listen to “Pump It Up” by Elvis Costello,” or, for a lighter version, “And She Was” by Talking Heads (where the bass lays out every other measure). You can really hear the rule’s effect here. Or try the Doobie Brothers‘ “Takin’ It to the Streets.” (All of those bands had truly great bassists.) Also worthy of a listen, for variations, is the bass line to Paul Simon‘s “Me and Julio” and all of the bass lines on his Graceland album (pointing back to the African origins of these rhythm combinations). For something a little more recent, try Rusted Root “Send Me on My Way.”

So that’s the rule. Learning to move from one root to the next, while reinforcing the kick drum, is the art of the Ivi’s. This trick is how the best Ivi’s transported their legacy from the city streets to the suburbs of the WASPy White Middle. They sneak in the African core beneath an innocent sounding melody. The art of movement within “the rule” became an art for virtuosos during the 1960s and 1970s. I suggest these four recordings, and I want you to listen to the busy, busy, busy bass lines on the first three, that perhaps you never really heard. I’ll bring it home with the fourth cut to show you the bones and essence of how to move someone’s ass and love the rule.

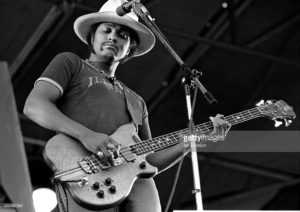

First, the single greatest bass line in the history of pop music is in “I Want You Back” by the Jackson 5. You’re surprised at how strongly I state this, but there would be widespread agreement among bass players. Ask one. Bass lines don’t get better. It is also wonderful and mysterious that we don’t know for certain who wrote and played it. It might have been Wilton Felder, or Bob Babbitt, or James Jamerson (my money is on Jamerson, but the debate is endless). The line is difficult to play . . . although that didn’t stop Jermaine Jackson from playing it, while singing, and doing choreographed dancing all at once . . . holy smokes! But the most important piece is the switch from punchy staccato ascension in the verses to the mournful legato descending scale in the choruses, followed by utter resolution with the bottom string below the chanted title line. This triple contrast, all while reinforcing the kick drum is the work of a genius. I dare you to sit still.

First, the single greatest bass line in the history of pop music is in “I Want You Back” by the Jackson 5. You’re surprised at how strongly I state this, but there would be widespread agreement among bass players. Ask one. Bass lines don’t get better. It is also wonderful and mysterious that we don’t know for certain who wrote and played it. It might have been Wilton Felder, or Bob Babbitt, or James Jamerson (my money is on Jamerson, but the debate is endless). The line is difficult to play . . . although that didn’t stop Jermaine Jackson from playing it, while singing, and doing choreographed dancing all at once . . . holy smokes! But the most important piece is the switch from punchy staccato ascension in the verses to the mournful legato descending scale in the choruses, followed by utter resolution with the bottom string below the chanted title line. This triple contrast, all while reinforcing the kick drum is the work of a genius. I dare you to sit still.

Second, I want you to listen to a line most people think was Bob Babbitt’s, but again, there’s a dispute. It’s on the song Jim Croce recorded called “I Got a Name.” In this case the drums are mixed lower and the bass is reinforced by the kick drum rather than reinforcing it. It gives the song its dynamism and moves it down the highway. The guitars do very ordinarily transitions between chords, but the bass wanders all around and over those transitions. Some of the licks are profoundly similar to “I Want You Back,” but in a different key. That may be evidence Bob Babbitt played both. Or that James Jamerson did. In “I Got a Name,” as in “I Want You back,” the piano is holding down much of the root-work, but the bass still works within “the rule.” Babbitt (or some other Ivi Leaguer) is even freer due to the doubling of the acoustic guitars and the regular left hand on the piano. In “I Want You Back,” the rhythm guitar is chinging high chords way up the neck, very rhythmic, but not much to move the ass. In the Croce recording, the bass can indulge its wanderlust.

Second, I want you to listen to a line most people think was Bob Babbitt’s, but again, there’s a dispute. It’s on the song Jim Croce recorded called “I Got a Name.” In this case the drums are mixed lower and the bass is reinforced by the kick drum rather than reinforcing it. It gives the song its dynamism and moves it down the highway. The guitars do very ordinarily transitions between chords, but the bass wanders all around and over those transitions. Some of the licks are profoundly similar to “I Want You Back,” but in a different key. That may be evidence Bob Babbitt played both. Or that James Jamerson did. In “I Got a Name,” as in “I Want You back,” the piano is holding down much of the root-work, but the bass still works within “the rule.” Babbitt (or some other Ivi Leaguer) is even freer due to the doubling of the acoustic guitars and the regular left hand on the piano. In “I Want You Back,” the rhythm guitar is chinging high chords way up the neck, very rhythmic, but not much to move the ass. In the Croce recording, the bass can indulge its wanderlust.

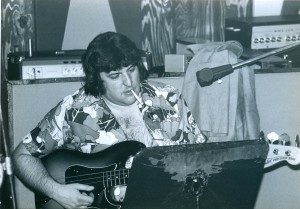

Third, and maybe the greatest surprise, if you never noticed it before, is the Ivi League line by Rob Stoner on Don McLean’s landmark song “American Pie.” It is even busier than Babbitt’s and/or Jamerson’s work above, but the most striking thing about the line is how amazingly loud it is in the mix. The recording art is very complicated, but this is what you could call a “four-dimensional mix.” Normally the bass could not be this loud without competing with (even cancelling) the vocal, but if the singer’s vocal timbre is just right (and McLean’s is), it punches through, so with the right balance of equalization and reverb, a good engineer and producer can get away with turning the bass louder. The sound is four- dimensional: closer-further vs. left and right, which feels like having the band in front of you. The amazing thing is that if you’re recording a work of art on the level of this song, perhaps the finest songwriting achievement of its time, it takes balls to have a bass line that loud and that busy.

Third, and maybe the greatest surprise, if you never noticed it before, is the Ivi League line by Rob Stoner on Don McLean’s landmark song “American Pie.” It is even busier than Babbitt’s and/or Jamerson’s work above, but the most striking thing about the line is how amazingly loud it is in the mix. The recording art is very complicated, but this is what you could call a “four-dimensional mix.” Normally the bass could not be this loud without competing with (even cancelling) the vocal, but if the singer’s vocal timbre is just right (and McLean’s is), it punches through, so with the right balance of equalization and reverb, a good engineer and producer can get away with turning the bass louder. The sound is four- dimensional: closer-further vs. left and right, which feels like having the band in front of you. The amazing thing is that if you’re recording a work of art on the level of this song, perhaps the finest songwriting achievement of its time, it takes balls to have a bass line that loud and that busy.

Everything about that song is ballsy, though –an almost nine-minute pop single? As above, the bassist benefits from a strong piano left hand pounding the chord root, and so Stoner is free to explore the mid-neck of the middle strings, saving the big low notes for emphasis on the stops and homecomings of the music. Rob Stoner must have been possessed when he played it. the line covers so much sonic space inside the kicks, from lagging on the back-most edge of the one and three, and then racing to the front edge, never settling in. (Thank-you, Mr. Pianoman.) The bass is played so freely and is so non-repetitive that I believe he improvised it. It doesn’t sound rehearse-able. One moment in particular makes me laugh. When McLean is singing the line “eight miles high and falling faaaaaaast” at about 4:16 to 4:23, Stoner plays an ascending glissando in the middle of a measure (very unusual), anticipating and preparing the ears (and the ass) for what the vocal will do three seconds later. Stoner follows this by a descending scale in perfect Baroque counterpoint to McLean’s vocal glissando on the word “fast.” It’s freaking hilarious.

Everything about that song is ballsy, though –an almost nine-minute pop single? As above, the bassist benefits from a strong piano left hand pounding the chord root, and so Stoner is free to explore the mid-neck of the middle strings, saving the big low notes for emphasis on the stops and homecomings of the music. Rob Stoner must have been possessed when he played it. the line covers so much sonic space inside the kicks, from lagging on the back-most edge of the one and three, and then racing to the front edge, never settling in. (Thank-you, Mr. Pianoman.) The bass is played so freely and is so non-repetitive that I believe he improvised it. It doesn’t sound rehearse-able. One moment in particular makes me laugh. When McLean is singing the line “eight miles high and falling faaaaaaast” at about 4:16 to 4:23, Stoner plays an ascending glissando in the middle of a measure (very unusual), anticipating and preparing the ears (and the ass) for what the vocal will do three seconds later. Stoner follows this by a descending scale in perfect Baroque counterpoint to McLean’s vocal glissando on the word “fast.” It’s freaking hilarious.

I could go on all day. Clearly. But let’s cut to the chase. This rule can be enacted with beautiful simplicity. We have arrived at the work of John Stockfish. He was Gordon Lightfoot‘s bassist, among other things. There are many examples of his simple genius. Listen to “Carefree Highway.” When you have a sweet or a powerful left hand laid upon your arrangement, you can move up an octave in the bass and as I have said, save the bottom end, the lowest notes, for home. This line, in its spareness, spectacularly chooses between the low and high register in expressing the chord roots, and yes, it growls where growling would seem otherwise unnatural. Tiny anticipations and early entries into moments of rest do all the work that the busier lines are doing in the Croce and McLean songs. This is a study in less is more. It is a cultural preference for understatement. I believe Stockfish could have gotten away with more. But the aesthetic decision in “Carefree Highway” was for sonic space, but also for strength and movement. Almost every Lightfoot recording Stockfish made is like this. You wanna learn how to play the bass with grace and taste, and still move peoples hearts and asses? Imitate John Stockfish. The parts are easy. Creating the parts, knowing what to not play? That takes a genius.

I could go on all day. Clearly. But let’s cut to the chase. This rule can be enacted with beautiful simplicity. We have arrived at the work of John Stockfish. He was Gordon Lightfoot‘s bassist, among other things. There are many examples of his simple genius. Listen to “Carefree Highway.” When you have a sweet or a powerful left hand laid upon your arrangement, you can move up an octave in the bass and as I have said, save the bottom end, the lowest notes, for home. This line, in its spareness, spectacularly chooses between the low and high register in expressing the chord roots, and yes, it growls where growling would seem otherwise unnatural. Tiny anticipations and early entries into moments of rest do all the work that the busier lines are doing in the Croce and McLean songs. This is a study in less is more. It is a cultural preference for understatement. I believe Stockfish could have gotten away with more. But the aesthetic decision in “Carefree Highway” was for sonic space, but also for strength and movement. Almost every Lightfoot recording Stockfish made is like this. You wanna learn how to play the bass with grace and taste, and still move peoples hearts and asses? Imitate John Stockfish. The parts are easy. Creating the parts, knowing what to not play? That takes a genius.

The mystery of what made North American popular music such a great cultural force in the world lies below the treble clef. So, as you are considering this Troubadour series, taking us from slave song to soul, over fifteen weeks, and beyond, do listen to the movement down below, the bass and its variations, the rhythmic elements and their tensions and releases. That’s where the roots of rhythm remain. It’s a story about how we begin to remember. And please do examine those bass and rhythm tracks on Paul Simon’s Graceland album. Most of what I will say is about African American music, albeit from an Anglo-American point of view. I wanted to start off with the stuff that really pulls me in, as a bass player. I am not trying to be neutral. But I don’t want to pretend I spent my life listening to blues and soul. I listened to rock and pop. I know the blues and soul, but what I put on the stereo is the kind of music I discussed here, and in the Prologue to this series.