Therapy for the Self-conscious Genius

Therapy for the Self-conscious Genius

by Randall Auxier

Artists must be punished. So says our twisted culture. Better still, they must punish themselves. A happy artist is no artist at all, we insist. Among all the artists, especially in the world of the macho 20th century, the men must be violent, the women desperate, and everyone suicidal. It gets really interesting for us when artists pair up, like Jackson Pollock and Lee Krasner, Diego Rivera and Frida Kahlo, Ted Hughes and Sylvia Plath, maybe Richard Burton and Elizabeth Taylor (I never thought they were acting in Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?; just a normal evening at home with Dick and Liz.) Are they really “artists”? With all that Shakespearean carrying on, yes, surely that must be art.

But what of, say, Paul Simon? That perpetually unhappy man?

We especially love it when artists are all screwed up and put it on display. We demand that too. That’s how we make sure they’re the real thing. When we elevate (“escalate”?) movie actors, or, yes, folksingers and pop musicians, to makers of “fine art” the paradox becomes sharp. This isn’t fine art. We went gaga for it when we were young and now want to feel it wasn’t vacuous. And we project our bad conscience about liking fluffy stuff onto our celebrities until they hollow themselves out for us. They want to be taken seriously, as artists, so they do it. And round the circle goes.

There is good news and bad news. Good news: what these poor kids create really is art. Bad news: it isn’t “fine art,” as we and these sufferers would have it be. Indeed, there is no such thing in any healthy culture. Such is Crispin Sartwell‘s argument. I agree. Art for art’s sake isn’t art in the richest sense. It doesn’t grow from what we are. It is vomited from the depths of what we are not but would be if we could. We came to identify this excrescence with “beauty.” As a symptom, Sartwell quotes Théophile Gathier: “Only those things that are altogether useless can be truly beautiful; anything that is useful is ugly, for it is the expression of some need, and the needs of man are base and disgusting.” (The Art of Living, p. 68) Having thus placed beauty on the throne, we later turned against beauty in the 20th century, as Arthur Danto documented. After all, what do we know?

This self-negation, this life-denying activity we call fine art in the West, in the last 250 years is the fruit of a cult: the cult of genius. It dates back to Goethe. As a young man he wrote a novel called The Sorrows of Young Werther, about a listless, silly young man who makes sketches of rustic life and writes bad poetry. He falls in love with an equally shallow young woman who is bethrothed to another, perfectly decent man. They pointlessly carry on until Werther can take no more of not having his beloved. So he kills himself, botching the effort, so it takes him a while to die. The novel has obvious formal flaws and weaknesses, but the young Europeans couldn’t get enough of it. They identified the hero with Goethe himself and everybody started imitating him. A bunch of frustrated boys killed themselves for love. It was awful. It was popular fiction gone south. This was 1774 and following decades.

Goethe soon hated the book. But people called him a “genius,” and the word was transformed. It once meant a spirit of creativity that inspires someone for a time, as in “Rembrandt had the genius of painting,” or “Handel has the genius of music.” Ethereal spirits that alight upon a person and deliver a very special ability. But now, “Mozart is a genius,” or “Goethe is a genius.” Hence, the nauseating rise of self-conscious “geniuses,” a whole generation of willful poets and artists thinking themselves misunderstood and under-appreciated by the dull masses who cannot fathom their artistic depths.

I don’t believe in “genius,” or in artists who simply must suffer for the sake of the gifts they bring. This is the flotsam of a sick civilization. Sartwell rightly points out that only in the Western world, and only in recent centuries, has anyone ever had the notion that artists are different from the rest of us and that they are hard to fathom. It’s basically crap we tell ourselves. Why?

Paul Simon wrote “I Am a Rock” before he was famous. He wrote “A Hazy Shade of Winter” after he was famous. Both use the same poetic trick. Most of the lyrics could be true of anyone, but there’s one or two lines where Paul pushes out the non-geniuses, reminding us that he is suffering in ways that only the genius can grasp. These are references to himself as the poet —he has his poetry to protect him, and his memory skips while looking over manuscripts of unpublished rhyme. I don’t know about you, but I don’t deal with my loneliness by writing poetry or poring over my own poetry manuscripts, or, indeed even arriving in a strange town to find people waiting for a poet (as in “Homeward Bound“).

Paul draws us in with common experience, but then reminds us that he’s the genius and we don’t understand how awful it is. He positioned himself as a prophet/poet from the very first. Surely it is hard to be the artist and genius in a time when everyone demands that such folks must suffer for their art. On the other hand, how bad is the problem? Especially after you make your first few millions? Seems to me you could just relax. And after all, you’re a very fine poet. Enjoy it, huh? But not if you believe the illusion you created. Life becomes the task of extending the illusion, wrapping it in an enigma, and perhaps being too busy (like Dylan) to go an collect your Nobel Prize.

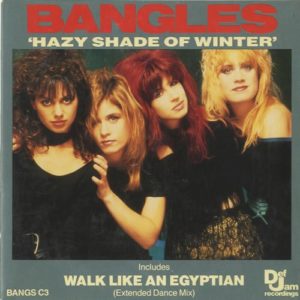

Wouldn’t it be better to use your “genius” for the benefit of others? Humble artists who don’t pose as geniuses, but whose work merits the judgment, get little attention. But they must live happier lives. When The Bangles recorded “Hazy Shade of Winter,” they left out the misunderstood poet part, and voir la, the song was now about anyone at all who needs hope. Not about misunderstood geniuses whining at their loneliness. Nice edit.