By Randall Auxier

Bob Dylan just won the Nobel Prize for literature. Folk music is hereby raised to fine art? Bosh. I think the division between fine art and “low” arts is artificial. Some of the best art I have ever seen (or heard or eaten) was made by people smugly labeled “artisans” by the mavins of haut couture. There should be a Nobel Prize for cooking, in my opinion. Anyone who doesn’t see that “folk art” is among the highest expressions of meaning isn’t paying attention.

The Navajo speak of the creation of the world itself as the weaving of Spider Grandmother and her mate. Is that low art? The “holy ones” created them as spirits and then later physical bodies were made to hold those spirits. Spider Woman discovered by accident that she had “string” within her, a spiritual power to make physical things, and she only gradually came to see that just by acting spontaneously, she creates patterns. Then Spider Man builds her a loom and she spins the human, cultural world too, which the Navajo call the “fourth World” or the “glittering world.”

And that is what we do when we make things from within ourselves. Our bodies direct the spiritual energy within us, and then, a pattern begins to emerge. Crispin Sartwell says that for the Navajo “most people were artists as we would understand the term: designing and weaving blankets, composing and preserving and performing songs, making ritual sand paintings” (Six Names of Beauty, pp 135-136). Then Sartwell says: “according to [Gary] Witherspoon, a person’s wealth was measured by the songs she created, which are bound to her identity in the way some cultures use names. Songs can actually be exchanged and form a kind of currency.” Cool!

So Bob Dylan is really named “Mr.-Tambourine-Man-Blowin’-in-the-wind-Masters-of-War-Desolation-Row-Don’t-Think-Twice . . . ” He has a very long name, so he must be a very wealthy man. I assume this is what the Nobel committee recognized. You may scoff at the idea of swapping songs for payment, but I know a place where that economy actually still exists, as an economy. The Kerrville Folk Festival is the yearly national convivium of poet-songwriters, eighteen days camping on a ranch in Texas and exchanging songs like money. These folks are rolling in the wealth of soul-webs spun from the strings of 5000 guitars and fiddles, and of course, vocal cords. Entry to a campfire circle costs you a song. A plate of lunch costs you a song. Even leaving a camp costs you a song.

The Navajo have a word for the times and places when all this making begets beauty: “hozho.” Sartwell says it is the most “comprehensive” word for beauty: all that is healthy and balanced and harmonious. The idea overcomes the binary oppositions we moderns tend to peddle. Light is very hozho, but so is darkness. Life is hozho, but so is death, in its season. Not everything is hozho, but anything can be, depending on its relations. There is no “outside” or wholly forbidden thing, since everything we make comes from within us, including what we make of that which we did not make.

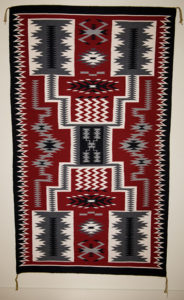

So, for us, the sunshine can be hozho, but also the storm. The rug pictured above is a storm, one of the most popular themes for Navajo rugs. The square in the center is the weaver’s home, or her loom, and it is connected to the four directions, and the four worlds, by lightning. There is rain and flowing water and the four sacred mountains of the Navajo homeland. Storms are dynamic and scary and also welcome in the dry Nation. Hozho.

This rug is just one complex thought. To think the storm is to live through its gathering, its onset, its duration, its passage, and its aftermath. There is no way to think “the storm” without its place, its hereness and its thereness, its height and its depth, the way it runs and the way it stands. It’s all in the thought, in the weave and in the weaving of it. The storm is the idea of the rug and thus, the rug is the storm, for us.

Writing songs is like that. There must be an idea, but there are limitless ways to frame it. Sometimes it’s hard to see what the idea is because of the way it is woven. Paul Simon’s song “Under African Skies” is hozho. You can feel it in the balance, the harmony, whether he is singing it with Linda Ronstadt (as on the studio recording), or, better, with Miriam Makeba at the Concert in Zimbabwe, when he changed some words for the context. I like those words better: “music rang round my grandmother’s door, take this girl from the Township of Mofolo.” The song is about “place,” in the strongest sense, but a storm is brewing there.

It is a Navajo rug of a song. One thought, many parts. The song sort of grows into existing. A single guitar arrives from a distance and is joined by the rhythmic steps of one walking. It breaks into language describing Joseph, who walks his days under the skies of Africa. Then there is a koan about memory and how it lives in the roots of rhythm, about falling into this life and pulsing with the power of love. Then comes the center, the eye of the storm, a lament about a displaced child, not home, and a prayer for “wings to fly through harmony.” This prayer granted, the one who prays vows to ask for nothing further. This child will never be home, but still may be hozho by singing, living, acting out harmony. Harmony in our world is woven from within and adorns the glittering world wherever we are.

After this thought, Paul repeats the koan about memory and rhythm, followed by (what I take to be) the granting of the prayer, a flying harmonic dance of sky and earth. Spider Woman weaves and Spider Man builds, ummmbada ummmbada woooo. A musical swell and then quietly we see to Joseph, walking into the distance. The last two verses are exact repetitions of the beginning, but now the storm has spent its fury and the words take on a different meaning. The song drifts away into silence like a storm passing, like a painful memory that stirs an anguished emotion and then fades.

I think Simon originally saw in his mind’s eye an image of a Native infant, a girl, displaced from her home, by Missionaries. How will she weave here, in this place she doesn’t belong, with no thread? She will sing and the melodies and the time that carries them will be her thread, and through harmony she will fly. The South African situation is only slightly different. These cities, teeming with displaced people, Tuscon, Johannesburg, don’t belong under these skies. They were put here by strangers and have made strangers of everyone. They are not beautiful or healthy. But the music almost redeems us.

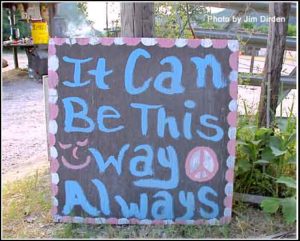

I don’t think Paul Simon will ever win a Nobel Prize. There are too many questions about credit for those who helped him weave the songs. These questions pertain to a time and a civilization that isn’t hozho when it comes to owning things. I like it better where songs are the currency and making them is the way of life, but I know it can’t always be that way.