The decade of the Harlem Renaissance was not only an important moment in American cultural history but, as Langston Hughes writes in his autobiography The Big Sea, it was a time in which even “the Negro was in vogue.” Hughes gives a vivid description of how precarious the social situation had become

White people began to come to Harlem in droves. For several years they packed the expensive Cotton Club on Lenox Avenue. But I was never there, because the Cotton Club was a Jim Crow club for gangsters and monied whites. They were not cordial to Negro patronage, unless you were a celebrity like Bojangles. So Harlem Negroes did not like the Cotton Club and never appreciated its Jim Crow policy in the very heart of their dark community. Nor did ordinary Negroes like the growing influx of whites toward Harlem after sundown, flooding the little cabarets and bars where formerly only colored people laughed and sang, and where now the strangers were given the best ringside tables to sit and stare at the Negro customers–like amusing animals in a zoo.[i]

There are many Bojangles today and we do not have to travel to their side of town in order to watch or hear them. African Americans have always been lead figures in America’s Church of Aesthetics, viewed as the prototypes in the phenomenology of coolness. One of the advantages of America’s diverse culture consists in the ability to create celebrities in Bojangles fashion. Stars and celebrities become the commercialized emblems of what can be realized or achieved by possible Americans. Enlarging the sense of American value and identity to include the successes of disinherited groups facilitates a symbolic complex of opportunity and freedom. It is without question that minorities remain at the frontier of American trans-media or the entertaining spectacle, which strives to represent an inclusive, hopeful, and healing capacity. People of all backgrounds identify with or are considered to be Black for the coolness and cultural capital that it symbolizes. This pattern of identity-exchanges further shows how Blackness is not on the same level with a white supremacy so historically and institutionally entrenched, but through this vast symbolism and the use of ironic relations the American aesthetic appeal has virtually made whiteness and Blackness synonymous. This advertises a fantasy-projected, abstract egalitarianism that papers over the evils of history. False impressions of racial reconciliation and atonement are constructed through these symbolic complexes.

Too many Americans naively take the displays of success as evidence for the elimination of racial disparities and challenges that minority groups continually face. Under such phantasms, the Blackness of African Americans becomes hidden or unconscious to the majority of whites, who naively portray virtual integration as just as personal and concrete as visceral relations. It is this irony that leads prominent whites and blacks to deny there is any difference between being black and white. A veil of egalitarianism is draped over the historical inertia of racial and ethnic inequality through the production of fame. Fame is a true equal-opportunity employer and gives the impression of post-racial harmonies and egalitarian pretensions! For example, actor Shemar Moore recently stated, “I’m just Shemar Moore the actor. I’m very proud to be Black, but I’m just as much Black as I am white.” Similarly, actress Zoe Saldana was quoted to have said, “there’s no such things as people of color.” These attitudes deny the Du Boisian “double consciousness” of Bojangles’ fame, as captured by Hughes in the night scene of 1920s Harlem that has been brought to bear on a global scale.

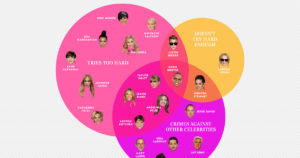

Modern celebrity and fame undoubtedly has a unique inner teleology. In order to understand it, we have to recognize how it functions beyond the mere extension of selves. Near the conclusion of Adventures of Ideas, Whitehead’s metaphysics of fame deals with this very structure. Fame demands nothing less than the anti-social impulse for “destruction of the audience.” Does it really matter to the star whether their thousands of followers and Twitter fans are real or just computer bots? Will we give euphoric praise to the athletes who perform acts of kindness for the audience and give us a glimpse of the humanity they still have left? The anti-social has to be distinguished from non-social tendencies. While non-social behaviors are not necessarily hostile or closed off to social relations, the same cannot be said of the anti-social. The pathos of fame necessitates the negation of tragedy or a common pathos we share in the suffering of others; celebrities are hyper-erotic selves who symbolize a life free from suffering and pain as the utilitarian fantasies that global capitalism sells to the world. Extensions of famous or “red carpet selves” take over the possible spaces and times of others. This is how they get everywhere you go! But with this extension of the self comes the self that can get lost or neglected. Society will build up these gods until they initiate the great crash or fall from grace that produces a new polarizing character.

Celebrities will continually remind us they are “normal” or “just like everybody else” as an antidote to this building firestorm. They must state the obvious just as one lays in a coma while loved ones in the waiting room have to be reminded that they are still holding on. A transition occurs from the non-social to the anti-social when they run out of places to flee that will console them. The judgment or paparazzi flashes of others becomes the lightening rod that triggers this reaction against the social order and they see themselves as banished or treated as if they betrayed their own societies. They never imagined that rising to stardom would come to be taken as a betrayal of the community and they will feel under trial and estrangement. This is how the hyper-eroticizing of fame is offset with a monstrous and unbearable tragedy. There is nowhere for the rich and famous to hide. All they can hope for is the passage of time, short memories, or another salacious infotainment diversion. From the heights of fame and legendary immortality, Jean Paul Sartre’s remark that “hell is other people” comes to its tragic realization. Like Shia LaBeouf or Jaden Smith, one wants to escape to another planet or would be happier as an “antichrist.” When rapper Tupac declared “F*** the World” (philosopher Nassim Taleb in his book Antifragile describes it as “F*** you money”) he uttered a key precept of the famous.

We should not be shocked then to find that celebrity marriages end in divorce given the categorical imperative that there can never be more than one superego at a time. When the endless shootings of Chicago and other instances of black-on-black crime are mentioned, too often the anti-sociality of fame is ignored as a motivating factor. Given the historical trauma and hauntedness of racial animosities in America we are quick to only see trends through the lens of racial injustices. African Americans are not killing each other because they are black! Only racists are eager to point out this coincidence and turn it into an absolute stereotype and pamper themselves with a false sense of superiority. It is far more likely, however, that young black males worship the John Gottis or Scarfaces as models of rebellious freedom and unrivaled success. In the heat of these scrimmages, these antagonisms are brought to the surface and exacerbated. The clash of superegos is a more realistic explanation for the disproportionate rates of violence we witness among black male youths. The paralysis of fame and anti-social attitudes permeates black neighborhoods given the ways America relies on the fame of music artists, sports athletes, and movie actors as a viable means to achieve social mobility and increased well-being. In a similar way that inner-city gangs adhere to a code of self-glorification and self-destructive pride, fame creates armies of authoritarian superegos. Just as surely as inner-city youth yearn to be future rappers or ball-players, hip-hop pop culture promotes the kinds of lust for fame and narcissism conducive to anti-social attitudes and lifestyles. How many of our kids are actually willing to shoot another over a Playstation game or a new $300 pair of Jordans?

Exaggerations of glory and glamour produce the kinds of “beef” driven by the anti-social sentiments. Like a God, one is aestheticized as being without an equal. No tragedy can be found which has not been overcome. Pride has always been the mark of the anti-social. In being banished from the Garden of Eden, Adam and Eve became the first superstars of the world through the curse of the anti-social. “I would rather reign than serve” is the devilish orientation of the famous. We also cannot fail to mention how fatigued and fragile the ego becomes with such high-maintenance. It is the possibility of embarrassment alone that maybe too difficult to take. When it is often said that the Michael Jackson’s of show biz “never had a childhood,” this means that they were sheltered from tragedies. Even the inner circles of these illustrious figures promote lifestyles of the anti-open. Paranoid, secluded, and distrustful of others are the symptoms of egophanic fame. They are likely to become trapped and enclosed in their own fiefdom that they later seek to escape–it is the inversion of the tyrant or authoritarian statesmen who hides and runs while wanting to gain more, whereas the famous are likely to give successes away for free which baffles their admirers and others.

Whitney Houston overdoses in 2012, while her 22-year old daughter Bobbi dies just 3 years later of alcoholism

Glorified ambition in the race to stardom births generations of neglected selves, or those envious of fame and indifferent to the “bread and circuses” of the crowds. One is anxious to give themselves over to popular heroism in the hopes of becoming a household name. Celebrity worship replaces any sense of respect or patience for the ordinary and routine of social life. One is constantly encouraged and pressured to embrace the uncanny, weird, and abnormal, often pushing it to reckless limits. Similar to the life of zoo animals, the existential structure underpinning fame actually promotes those anti-social sentiments that lead one to become a kind of J.D. Salinger or Miles Davis of life—a recluse in hiding who doesn’t even want the world to see their works of genius anymore. Such individuals look to produce monological art, in Nietzsche’s sense, with no need for witnesses or an audience. The celebrity annihilates or becomes indifferent to the crowd over their careers. Today through social media, we are more likely to hypercognize virtual audiences in our feeds and posts that allows for a communicative loop that feels entirely self-referenced! No wonder we are coming to expect that an anti-social psychopath or misanthrope is the one typing behind the keyboard.

Famous selves increasingly run the risk of self-abandonment. Celebrities represent that race of humans who quickly run out of places for self-harboring. When the self is identified and defined in terms of being other-directed, it very likely that one will float off or be lost at sea, so to speak. Superstars will complain about the ability to go out and just grab a bite or watch a show without having to be noticed. From the outside-in, they look as free as soaring eagles, while on the inside they feel trapped and agitatedly cornered. The real cost of celebrity involves how the performance replaces the performer—quality of production or what they are “working on next” becomes more important. Like Marx’s “alien superworkers” civilized societies feed on this energy of fame without regard for the needs and interests of the individuals actually on the stage. This creates an institution of liars who brag about who they know or met and got to hangout with in the pantheon of stars. Celebrity generates the sacred times and spaces of culture that stand juxtaposed to the profane domains of the crowd. Reality is viewed from the cheap seats, and even though the stars appear far away and small they remain quite grand. As a result members of the crowd receive recognition by way of affiliation with the signs and symbols that the hyperbole of fame sanctifies. We not only socially promote these brands and lifestyles, but also establish our identities, values, and fidelities with others around them.

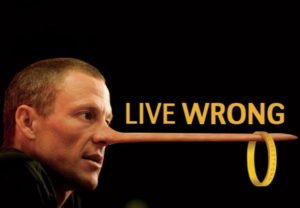

After years of denial and destroying people’s lives, cyclist Lance Armstrong publicly admits to doping in 2012

The costs of fame or to live the life of a Bojangles entail the struggle of hyperbolic conceit and vanities. Like money, fame has a way of ignoring injustices and tragedies in the world and becomes oblivious to the ways it actually furthers them. From terrorists to cartel or gang leaders, what if the escalating penchant for violence has more to do with the desire for fame and an anti-social stubbornness which vows not be bettered? If most kids think and act in ways that emulate the superegos of celebrity culture then will they be prone to perform anti-social acts and rituals? This is a larger cultural problem of American consciousness. Nearly everyone in America has this outside-of-themselves perspective and is overly self-conscious about eyes being on them. Practically all Americans are instant stars once they step foot on foreign soil! America’s cult of success promotes the practice of marketing companies and products ideally, without any traces of tragedy—the food will always look better in the commercial than what you actually get. Even under Obama’s drone policy, the US is the leading nation in the race to sanitize war or toward the “clean war ethos,” a process by which the objectives of war are achieved without having to endure the sacrifices or risks in the conflict. As our gadgets provide more of our worlds at our fingertips, Americans will continually find social encounters intrusive as they dwell in their masterless privacy zones.

This capacity is potentially created through the power of the image, which Heidegger argued in his 1938 essay entitled “The Age of the World Picture” is the dominant form by which the world undergoes conquest today. It may not be the case that we “saved” Prince or Michael Jackson from his tragic death, for example, but a live virtual hologram of the pop star can imitate life just enough to make us suspend disbelief and hope for a future relieved of such tragedies. The transportable images on the screens of our devices and gadgets portray the illusion or organic semblance of this urge and ability to control life by anti-social means. From the special effects of cinema or exaggerations of self-portrayal in music videos, to cheat codes and endless do-overs or “lives” on video games speak to the powerful appeal of this illusion in modern society. Genetically modified foods that can be ingested without individuals incurring calories or commercials advertising new medicines that provide exhaustive lists of a drug’s side effects, are obvious examples of civilized societies’ striving to always outdo nature’s tragedies. Americans will have to face the issue of whether we are becoming more anti-social as a whole with our unmatched erotic obsession for fame and the appearance to avoid tragedy.

[i] Langston Hughes, The Big Sea (New York: Hill and Wang, 1940).