It is no secret that we live in an age of disruption and distraction—I am easily reminded of how regularly “breaking news” alerts buzz across our screens, above crawlers with overloads of useless information. Almost anyone today has the tools necessary to emulate the watchdog function of the media. That is why I was startled to hear Dr. Robert P. Moses claim, at a public lecture entitled “We the People: Constitutional Personhood in our Time,” that America has a grim prospect of ever addressing its racial and socioeconomic injustices. Without batting an eye, he responded to a question from the audience with a scathing critique of our media-obsessed society: “There are no effective forms of mass organization in America today. For what would need to happen would have to occur outside of the media.” This was a shock! Surely, Dr. Moses knew about the power of Twitter and other social media. But here was the architect of Freedom Summer and lifelong humanitarian teaching us something about ourselves and the lesson left a room of roughly three-hundred silently agitated.

It immediately dawned on me that this is not the way Americans think of themselves! With a can-do attitude of “get er’ done,” it seems there is little that can deter such a motivated people. We are open and organized enough to face the challenges of global proportions, at least one likes to presume. It got me to thinking about the ways in which we confront social injustices and controversial issues. We are good at drafting broad public policies like the Affordable Care Act (ACA) or No Child Left Behind (NCLB) with major PR spin. The same pattern emerges that creates the next big attraction for our viewing pleasure. Could it be the case, as Bob Moses suggests, that Americans are better at performance than the real thing, and we have gotten so caught up in transmedia that we barely seem to notice we are still in costume?

The dangerous tendency of our information technological epoch is that we ironically exaggerate our ability to organize and communicate—key ingredients for grassroots struggle. It should come as no surprise that mainstream America thinks that real change comes from the top-down, through corporate or monopolistic structures—in the coverage after the stories occur. At the same time, there is a built-in aversion to movements such as the Million Man March or Occupy Wall Street which are perceived as “threatening.” The only acceptable forms of social upheaval, by mainstream standards are in the history books through a romantic nostalgia for the past.

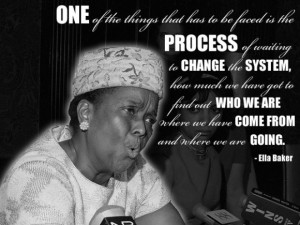

As Dr. Moses recounts in his memoir Radical Equations—Civil Rights from Mississippi to the Algebra Project, the major problem with leaders like Malcolm X or King is that the organizations they ran failed to make personal connections on the ground through intimate engagement. Instead of listening and speaking with others, they were more concerned with being heard and using the limelight of the press as the catalyst of the civil rights movement. Moses believes we would do well to remember the wisdom of Ella J. Baker who criticized these hierarchical approaches because they handicap “oppressed people to depend so largely on a leader, because unfortunately in our culture, the charismatic leader usually becomes a leader because he has found a spot in the public limelight. It usually means that the media made him and the media may undo him.”

Americans are more concerned with sponsorship and public relations than doing the work of community organizing. Much of the way Americans conceive of freedom is highly distant and abstract as it relates to the common person. Media spaces are created for the purpose of symbolizing this freedom through celebrity and fame. It is a freedom fit for celebrities and other stars, but this is merely an appearance, or semblance of liberty. Under the mask and deception are the regularities of inefficiency and waste, the same lethargic system as King noted that “takes necessities away from the masses to give luxuries to the classes.” America has a Black president, for example, and the hope is that you will take the symbol as the real source of change without regard to the explicit factors. But this kind of satisfaction is admittedly as fleeting and low-risk as American patience or resolve. From Rodney King, Amadou Diallo, to Treyvon Martin and Eric Gardener, America has an industry of examples of media aestheticizing the complexities of race relations in America so that it can be packaged and sold to the world that we openly and collectively deal with the ugliness of our issues. It creates the façade of transparency, sincere convictions, and the rhythms of change. One is reminded of Thoreau’s famous phrase, “improved means to an unimproved end.”

It is not surprising, therefore, that following King and Malcolm’s assassinations the movement for civil rights was sterilized; new figureheads like Jackson, Jr. and Sharpton filled in the vacant media space. There were victories like the Civil Rights Acts of 1964 and 1968 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965, but did that end the overwhelming poverty and lack of educational opportunities or desegregate American neighborhoods, schools, and prisons? It doesn’t take an expert to admit that these achievements have more of an abstract impact with little improvement in concrete conditions.

If mass protests and other forms of civil disobedience emerge they are likely to devolve into infotainment—another hashtag movement to receive the approval of political correctness—that is the lifeless routine. The recent riots over the shooting of Michael Brown in Ferguson, Missouri offers a clear case in point. Aside from fear-mongering images of violence and stars like Cornel West being arrested or Sharpton giving speeches in demonstrations for the cameras, will anything meaningful—and I mean radically, to the root cause—come of the matter? Unfortunately, the media won’t hold on long enough for you to find out—they have to move on to another victim, another abstraction and more mind-numbing coverage. But our aim should not be to abstract away from our concrete conditions which is easy to do under virtual integration and our hyper-sensitive aestheticized culture, but to question the concreteness of our abstractions.

This aesthetic structure of virtual integration led by mainstream America is then moralized to other peoples and leaders of the world; they are pressured and lured into American grandstanding. For example, Obama answers the New York Times reporters’ questions on a recent state trip to China while the Chinese president Xi Jinping ignores him, and somehow this makes us morally superior. This is extremely delusional! Meaningful and constructive dialogue is not taking place on the ground in our neighborhoods—the only time you will see a Republican or Democrat in your neighborhood is around election time. Our various forms of transmedia encourage us to talk past each other with our minds made up. Nobody really challenges the views they already hold dear! We not only aestheticize controversial issues, but we wallow in our own propaganda without much of a challenge to our own views and positions. The overemphasis on the aesthetic leads us to evade the integrity of our moral obligations and traps us in the present.

Aesthetic spaces that pervade our transmedia and virtual integration are dominated by concern for the present moment. When we aestheticize our experience we become absorbed in the ever-present now. That is why it is so easy to forget about what received around the clock news coverage on a story that happened just last week, or we will listen to a song repeatedly or watch the same movie for the umpteenth time. No sense of continuity is established through aesthetic mediums because they have a character that contracts us to being taken in by the moment. Aesthetic reality wears blinders, so to speak, and has the force of solipsistic experience in which you are enchanted by the here and now.

Unlike being captivated by what’s merely at hand, moral experience is relevant to our future action—what we will do and how it will get done. Morality has to do with the commitment and consequences of our actions. Whereas aesthetic experience makes the past and future negligible, moral experience has to do with future relevance and the potential value that will be achieved or realized. There is a temporal continuity assumed in our moral realities that is not prevalent to our aesthetic feelings. By the moral we are drawn into the otherness of the other, while the aesthetic lures us into what G.W.F Hegel called the “sensuous show.”

Our leaders and people of privilege struggle to recognize, let alone relate to the stories of the disinherited. This does not mean they are not good at symbolizing such struggle and sacrifice through a play on pathos and feelings. But such depictions are concerned more with figureheads and the niceties of media spaces—the very spaces that create the illusion of moral will and authority. Americans are good at causing a stir, starting a bunch of ads, and sensationalizing major issues. But is one really dealing with the complexities of the world through aestheticizing alone? It is time well over due that we turn to the wisdom of Dr. Moses or Ella Baker and their premonition that the same media that has made us will soon enough break us. American transmedia serves as the “charismatic leader” Ella warned about who act as the PR reps for the defenseless and innocent.

It is reasonable to be concerned with America’s endurance to face its moral challenges. What does the massive impatience and culmination of our experience into the present captivation (whatever it is) say about American resolve? It shows that we are good at creating aesthetic spaces and drawing attention to images and memes, without stepping away or refusing to pay attention long enough to address our most pressing moral perplexities.