Isn’t It Rich?

by Randall Auxier

This fellow stands out in a crowd. I’ll bet he wants it that way. Most of us would be unable to connect with him. Say, you and me are having coffee and he wanders into the Starbucks. Are we allowed to stare? Surely the answer is “yes, you may even gawk.” A person who is made uncomfortable by a few stares does not work this hard to attract them. Our question to him and to ourselves is: “Dude?”

We all have our ways of self-presentation, don’t we? We send the signals we choose. There’s no point in pretending we don’t know what we’re doing. We choose our stylings, and we set up barriers to other people, little signs that say “you think you know about me? Well, you don’t.” This isn’t just about flying your freak flag, it’s about making the world pay an admission fee if it wants to get beyond your surface. We all want to be known, but if we make it too easy, it’s as if we don’t place a high enough value on our own inner lives. If anyone wants a connection, it needs to be real. These days real connections don’t happen in an instant and they don’t last without pain.

This dude knows something about pain. I am told that some of these piercings are essentially surgical. Most of that brightly colored skin is tattoo work, not make-up. An astute individual asks “how does he shave?” Another responds, “are we sure it’s a ‘he’?” Gosh I don’t know, but I’m guessing this individual has heard it all before. It is hard to view this image without wondering what takes a person down this path. So how do you become friends with this person, and if you manage to become friends, do you go places? The movies? The bar? Sailing? (Be careful not to get one of those rings caught in a halyard!)

Maybe he is wearing on the outside what we all conceal on the inside. Would anyone be willing to form a voluntary connection with you if the symbols of your inner life were so many colors and objects dangling from your face? In a way, our inner lives do show in our physiognomy. We say someone has a “care worn face,” or a walk that is “world weary,” or a posture of defeat. These are genuine externalizations, I’m sure, but they have more to do with chronic trends in our emotional well being. They aren’t markers of episodes in our lives. It is interesting to me that younger folks have taken to getting discursive tattoos relating to episodes in their lives –a death, a break up, a victory. I wouldn’t do it, but maybe I’m repressed. No, not maybe.

Perhaps the basic urge this fellow chose to follow is becoming more acceptable. The clown, the jester, and the trickster, are cultural archetypes found in every historical human group. These types wear bright colors and stand out in a crowd. They don’t conform to ordinary social pressures and they perform the important service of saying what others can’t or won’t say. They know our deeper motives, and they see what lives and breathes within our souls that we don’t recognize in ourselves. Maybe people have always had a hard time with the disconnect between their own inner and outer lives. If not, why the clowns?

By standing outside of the circle of the normal, the jester gets a clearer view of our folly, but clowns pay for that view by becoming essentially alone among us. To wear on the outside what we all feel on the inside sacrifices one kind of connection for the sake of another. Yet, the figure is made sacred because it is an inside-out image of ourselves, showing us our boundaries. Everyone knows that comedians aren’t happy people; they are those among us who take their pain and twist it into joy, since feeling like you’re alive is just the flipside of feeling yourself dying. Comedians do in language what clowns do physically: they turn inside out for us. And laughter hovers between life and death. This is our existential predicament. The creation of culture itself is a response to it. We feel ourselves dying and we want death. We feel ourselves living and we want life. We look desperately around for something that will live on when we are gone and for something that will get it over with right now.

That predicament is the heart of ritual and of myth. The dance and the story do the needed work. Traditional peoples who live in the ways of the ages get this. When preparations have been done just right, and when the circle of the people is complete, the god appears in the midst. The god is neither dead nor alive, is exactly the same on the inside and the outside, and the god is what we are, or would be, if we weren’t trapped in an endless cycle of mortal pain. A few of us face the pain, welcome the pain, shake an angry fist and dare it to do its worst. Most of us don’t do that. Most of us want this fellow above to do that sort of thing while we watch him tempt death into a game of tag.

For traditional peoples, being connected to others was a deep given, not an achievement. Everyone knew everyone in the group, and the distance between inner and outer life was minimal. The dance, the story, the song, and the god who comes, were enough to restore balance for a season. But the seasons change and the people forget the god. The pressure builds from within and without for us to prepare our hearts and our village for the return of a god. And the humans always did that, and the god came when we called, if we called the right name at the right time.

The tension still builds among the moderns, but we have forgotten how to remember. We don’t listen to the elders. We believe they are gone, that death is something final, that we, the living, are alone. It makes us crazy and it makes us dangerous. Our science is stupidity and our wisdom is folly, so we kill everything that reminds us of our own humanity. John Fire Lame Deer, the Lakota Holy Man, and one of the founders of the American Indian Movement, was a rodeo clown, a convict, a Casanova, a drunk, and most of all, a whisper of memory in the quiet of a perfect starry night. I will spend the next several posts working through his vision.

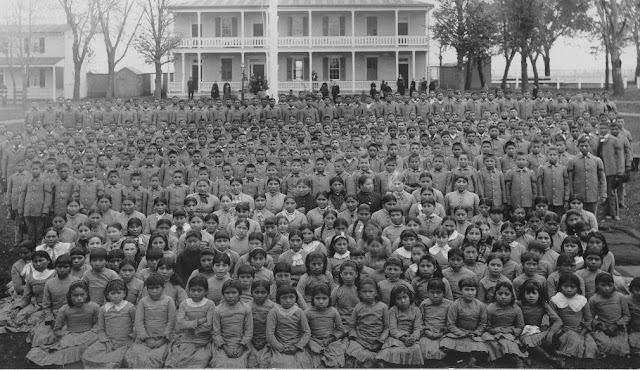

We should start at the beginning. Lame Deer wasn’t in this picture, but he learned the roots of our modern pathology at a school like this one, where native children were forbidden to be what humans had always been. They were taught to fear the difference between what was in them and what was around them. They were taught that the god would not appear in the circle of their people. They were taught to feel as afraid and worthless as their modern brothers and sisters, nay, more so. Why?