Co-Author: Laura J. Mueller

It has become all too normal that what the average American citizen refers to as a “national tragedy,” such as police-initiated homicides of the unarmed, or mass shootings, is treated in predictably routine, hollow fashion. The oxymoronic tension between the tragedy and its therapeutic treatment is the New American Norm. The outpouring of emotion, solidarity, and pleas for justice and peace through social media incitements following these events look uncomfortably comfortable. We commonly know that these “responses” (if we may call them such) rarely rise above personal fascinations and agitations. A manifesto of personal growth and privilege hides behind a plea for justice and peace. Americans seek to get involved in the existential crises of others, but only from a distance without any real personal involvement. Social media acts today as the vaccine of cultural tragedies—like a trip to the doctor, it is the preferred means of daily immunizations from the horrors of the world. And, lest these social media warriors for justice are forgotten as the “progressive, forward-thinking” souls they are, another shooting occurs as a booster shot for personal morale. We construct these immune-bubbles, more concerned with our own personal hygiene than willing to make the sacrifices necessary to fight against true social injustices. Anyone who acts today in any shape or fashion will be seen as threatening and considered the radicals and extremists.

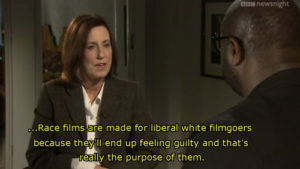

There is a strong form of passivity that accompanies the will to aestheticize, a form that the social media warriors of the world have nigh unto perfection. In a culture bent on aesthetic fetishes, the impulse to act or engage is transformed into the desire to witness, or just to be on the scene. The Panopticon lives on in Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram. More of us have grown accustomed to folks who would prefer to capture or record an altercation rather than attempt to break one up and strive to keep the peace! We would prefer to be the witnesses rather than the witnessed, and in doing so, are succumbing to the lure of being the witless. Too many of us treat the tragedies endured by others as if it were a drama in the Roman amphitheaters or a cinema matinee we attend for amusement. A sense of compassion or horror may even grip us for a time but, like spectators who engage through detached arousals, it is often short-lived. It is similar to attending a movie and circus and experiencing the momentary loss of yourself—for a short time you lose track and forget you’re actually at a show because you have been so engulfed and transfixed by the drama unfolding in front of you. But unlike the theater or circus, you don’t need to buy a ticket for admission because no one is allowed to leave this coliseum, even if you go offline for a while. People’s daily traumas and catastrophes are the new scripts, and will replace the need for actors, directors, or special effects. It is a global, around the clock eagerness to allow none to escape the games. It is reminiscent of 1970s blaxpoitation cinema, it is the daily witnessing of Jesse Washington’s lynching in a sick eternal recurrence, it becomes another use of black bodies to serve white conscience.

This kind of hyper-cinema speaks to that American apparatus obsessed with live-feeds, ego-technic apps, and transmedia telecommunications. This new form of entertainment will relegate movies, video games and reality-TV as second-rate, less valuable diversions. Hyper-cinema is the dominant American genre of sporting today–a kind of Roman coliseum 2.0–America’s current Church of Aesthetics. Social media like Facebook provides the virtual terminals to broadcast, transmit, and archive the giving (sharing) and taking (using) of proto-scenes. And our personal involvements or commitments are viewed with the same kind of indifference as the lives we can so easily aestheticize. Who needs Hollywood when you can have the “real thing”? Are people not thirsty for the consumption of blood, violence, sex, terrorism, and death like in the Roman amphitheaters? The sensationalism and horror of real-time aesthetics is the new game to be played, stimulated by a kind of heroism for successful competition and survival. It has become the new form of expression in postmodern high-culture. We will look to the crowds to give the thumbs up or down, as all authorities will be challenged to prove themselves in the arena. As we take off our masks and merge fantasy with reality, we will steadily beam in on the micro-dramas of the world and be sucked-in to the daily soap operas we view with a luxury-box pessimism.

Bentham’s Panopticon has become Foucault’s vision: hyper-cinematic America and its social media platform has become a lens of the invisible omniscience. We view others, and ourselves, as if from afar, categorizing the appropriate responses to these tragedies and quarantining those who do not comply. Thank god for the flu shot, and thank god for Alton Sterling, Philando Castile, Eric Garner, and countless other Black Americans whose public deaths allow us to remain immune from perceived callousness! If we post the right video, and “outpour” our love and “support” enough, we can escape quarantine once more.

The simple fact of the matter is that Black abuse, and white-on-Black violence, has always been a way to purge white conscience, has always served as a scapegoat for white Americans, whether or not the process is wanted or realized. bell hooks’ recounting of feminism, slavery, and abolition in Ain’t I a Woman gives us that harrowing tale of whites’ prevailing concern for their own morality, above and beyond the experiences of slaves as real persons, in real situations. Both hooks and philosopher Angela Davis tell us how Black men and women were the scapegoats of white violence, forced into protecting with their bodies and lives the “moral and pure” white woman, who watched flagellations and rapes from afar, knowing if it isn’t this woman, it could instead be her. Black women and men have served as symbols of radical alterities, whose abuses and deaths historically have been stand-ins for the violence white people could just as well commit upon each other. Witness the violence, pray through the rosary, genuflect, and provide an “outpouring” of love and support to remedy a system that you still perpetuate. Souls cannot be saved if there is nothing from which to save them! How can God forgive your sins if they aren’t first committed? The consumption and perpetuation of horror prevails and provides Americans an opportunity to take the antidote and purify themselves once more. Today’s “social justice warrior,” who uses social media as a platform and a voice, might indeed have something worth saying. Of course we need to support our brothers and sisters of all colors. We’re all in this together, but we cannot forget what that really means. What this really means is that the social justice warrior cannot be only in it when something has been hyper-cinematically presented to the world; we are all in it down to each small act of micro-aggression.

George Orwell feared that, through rapid technological advancement, an outside source could use such technology to make society a prison of itself, much like presented in 1984

Americans now wear empathy like a Greek persona or mask, wearing it when it serves a purpose and removing it only when the audience has left the amphitheater. Participation in our New Cinematic World demands we wear a mask of empathy lest we be jeered offstage.

Where there is lack of conviction, cynicism is bound to spread and escalate. Aristotle taught in the Poetics that tragedy is a cathartic process of humbling and healing oneself. But unlike in Aristotle’s day, our experiences with tragedy are transpersonal and interlocked with the suffering of real people, in a real plot and not one merely rehearsed with paid actors. There is an uncanny responsibility to intervene on behalf of those one does not know, or even know anything about, but must take their word for it. The difference between the stage and audience has been blurred or effaced. We cannot afford to be detached onlookers without violating the moral imperative that we must act on behalf of the “story.” Life has become a process of proto-scenes forcing their way into our sheltered lives demanding to be addressed beyond the trivial desire to hyper-cinemize. The new pragmatism will tolerate nothing less than real immersion in the struggles and shifting allegiances, in which not even those who wish to only remain members of the crowd can escape the fate of self-sacrifice. None can claim innocence by curiously indulging in the atrocity consumption of hyper-cinema or pretend they “choose to ignore” these cultural calamities without contributing to their violence-induced productions. America needs less actors and industries of aesthetic enablers and more communities of personal action and persistence response. Americans can no longer afford to hide their faces behind an empathetic persona; they are now tasked with removing the masks, and getting their hands dirty.