Not by Bread Alone

by Randall Auxier

Emma Goldman spent two years in the dank prison on Blackwell’s Island (now called Roosevelt Island) for saying in a speech to a group of workers: “Give us work. If you do not give us work, then give us bread; if you do not give us either work or bread, then we shall take bread.” Two years in the dark for that. She advocates the very crime of Jean Valjean, does she not? While Anne Hathaway enjoys her Oscar, I am left wondering whether the chant of the Paris Commune in 1871, “Down with Jean Valean!” might not more aptly capture the problem, but more on that in a moment. With the legal system of New York in the role of Javert, how does the American tale of The Miserable unfold?

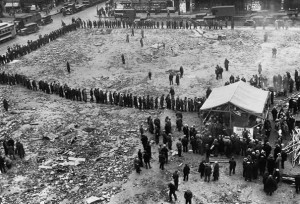

It is Depression Era New York City, and this bread line is so very orderly. Someone told these men to stand in a square, or perhaps they’re just used to it –a hundred days like this one before. People don’t form perfect squares spontaneously, hungry people least of all. I guess we’ve all been hungry, but few of us quite so much as these people. If this is not a picture of profound respect for law, for order, for authority, and for private property, well, I don’t know what is. And people in New York City starved to death, peacefully, in plain sight of food. I can’t support that kind of respect for private property, although I admit I also don’t know what to say to Emma Goldman. If she stepped into the middle of this square of hungry people and began to speak, I have a feeling that not just the geometry would suffer, so would the bakery and the delicatessen that is surely within a block or two of this gathering.

But then the question: How long do you have to wait between asking for work and asking for bread? “Until you get hungry” errs on the side of permissiveness, but “until you starve” is too long. Still, the time between asking for bread and taking bread is short. And here lies the whole dilemma. In a very real sense, the citizens in this line have asked for bread, and they are receiving bread. I hope ardently there was enough to go around that day because the respect for private property being displayed here by these hungry people, and for the society’s need for that kind of order, moves me to tears. Will you not feed these people? How patient and how respectful do they have to be?

In 1894 Voltairine de Cleyre gave a spirited defense of Emma Goldman’s actions. Did Goldman incite a riot? Probably that is true. Are her words protected by the First Amendment? Probably not. Plenty of anarchists (not Emma) hold private property in high esteem, but de Cleyre says it is privilege and power that annihilate the right of and the right in private property. When appropriation extends to the accumulation of unlimited wealth, to infinity, private property really no longer exists. What exists is unjustifiable power of some over others, since that is what infinite private property has become. As de Cleyre says, she believes that in any rational world, the bread already belongs to the hungry. They haven’t stolen it, indeed cannot steal it, especially when their labor has made it. Unlimited capitalism expropriates food from the hungry, not vice-versa. Those who really wish to assert private property as a right must resist those who would convert property into a kind of power that destroys individuals.

When the Paris Commune chanted against Victor Hugo’s character, it was because Jean Valjean became a bourgeois and thus an enemy of the revolutionary class. Hugo himself was a staunch republican and, as his countrymen well knew, a supporter of private property, a romantic individualist, and pretty much the opposite of a communist. Thinking across generations, Hugo had more in common with Barry Goldwater than with Emma Goldman. The American Miserable have some strange company, if Goldwater writes their tale. After the Commune was ousted and its leaders shot, Hugo founded the first major organization for the protection of artists’ copyrights. He would have hated Napster and Torrent. But de Cleyre believed in private property, and in justice, in about the same degree as Hugo.

The difference between de Cleyre and Goldman is a contrast of self-reflection and commitment. A person who is self-reflective learns about the world by suffering it from the inside out. Self-doubt, humility, and empathy are the path of education, and self-generated psychological pain is the wooden ruler that both measures our gains and raps the back of our hands when we have gone astray. These travelers are what Jung called introverts, and they are more vulnerable to their own negative judgment than to the world’s disapproval.

Goldman, on the other hand, learns the world from the outside in. The power exercised over her by others, especially early in her life, was met with resistance rather than self-reflection. People like Goldman will be likely to see problems as residing in the world, not in their own response to the world. Where de Cleyre encourages us to see that the solution lies in ourselves, Goldman points an accusing finger in the opposite direction. Goldman is what Jung calls an extravert, vulnerable more to the world’s judgment (and judge her it did) than to her own doubts.

When I think about great spirits in history, I look for pairs like Goldman and de Cleyre. Emerson is the extravert, Thoreau his counter-balance. And what about the time that Theodore Roosevelt spent alone with John Muir? That would have been an interesting exchange. The scales don’t balance, in the end, though. Extraverts are far more likely to become leaders, I believe, and they find it far more difficult to empathize, to learn humility, to admit fault, to experience warranted self-doubt. Their confidence comes at the expense of a rich inner life. We admire them for the virtue of commitment, at least when they are consistent and honest.

Today’s world doesn’t reward people who are humble or self-conscious. But I think those who are reserved, self-reflective, and slow to decide, ultimately can exceed extraverts in the virtue of commitment. Empathy with others initially threatens our psychological survival, but for those who can endure it, the individual strength that is gained becomes unshakable. Having overcome their own self-judgment, which was harsher than anything the world could offer, the world has no power over them.

I think many of the world’s saints, martyrs, and messiahs are of this sort, including Moses, Jesus, Muhammad, the Buddha, St. Francis, St. Claire, Gandhi, St. Edith Stein, and a host of others, including Voltairine de Cleyre, whose names are less well known. Something about holding oneself to a higher standard than the world can impose has the effect of purification, and it seems to be an ordeal we face mainly alone. It is a confrontation with solitariness.

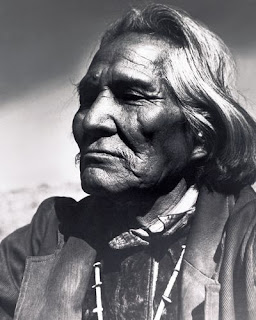

This individual below certainly looks like such a soul. You will be surprised, I think, to learn more about this picture in my next entry.